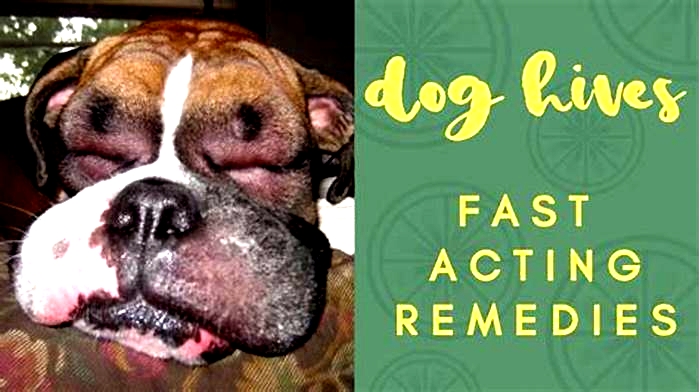

Does vitamin D reduce hives

Vitamin D provides relief for those with chronic hives, study shows

A study by researchers at the University of Nebraska Medical Center shows vitamin D as an add-on therapy could provide some relief for chronic hives, a condition with no cure and few treatment options. An allergic skin condition, chronic hives create red, itchy welts on the skin and sometimes swelling. They can occur daily and last longer than six weeks, even years.

Jill Poole, M.D., associate professor in the UNMC Department of Internal Medicine, was principal investigator of a study in the Feb. 7 edition of the Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. The two-year study looked at the role of over-the-counter vitamin D3 as a supplemental treatment for chronic hives.

Over 12 weeks, 38 study participants daily took a triple-drug combination of allergy medications (one prescription and two over-the-counter drugs) and one vitamin D3, an over-the-counter supplement. Half of the patient's took 600 IUs of vitamin D3 and the other half took 4000 IUs.

Researchers found after just one week, the severity of patients' symptoms decreased by 33 percent for both groups. But at the end of three months, the group taking 4000 IUs of vitamin D3 had a further 40 percent decrease in severity of their hives. The low vitamin D3 treatment group had no further improvement after the first week.

"We consider the results in patients a significant improvement," Dr. Poole said. "This higher dosing of readily available vitamin D3 shows promise without adverse effects. Vitamin D3 could be considered a safe and potentially beneficial therapy.

"It was not a cure, but it showed benefit when added to anti-allergy medications. Patients taking the higher dose had less severe hives -- they didn't have as many hives and had a decrease in the number of days a week they had hives.

In the study, patients had suffered from five to 20 years with severe hives. Some had been on therapy and others none.

The cause of hives is not generally known, but allergy and autoimmune reactions sometimes play a role. Treatment options for chronic hives are limited.

"Standard therapy is to control symptoms with antihistamines and other allergy medications," Dr. Poole said. "Some are costly and can pose substantial side effects."

She said the study didn't include patients with kidney disease or those with calcium disorders.

Relationship between vitamin D and chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review

Clin Transl Allergy. 2018; 8: 51.

Relationship between vitamin D and chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review

,

1,

1

1,

1,

1and

2Papapit Tuchinda

1Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, 2 Wanglang Road, Bangkoknoi, Bangkok, 10700 Thailand

Kanokvalai Kulthanan

1Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, 2 Wanglang Road, Bangkoknoi, Bangkok, 10700 Thailand

Leena Chularojanamontri

1Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, 2 Wanglang Road, Bangkoknoi, Bangkok, 10700 Thailand

Sittiroj Arunkajohnsak

1Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, 2 Wanglang Road, Bangkoknoi, Bangkok, 10700 Thailand

Sutin Sriussadaporn

2Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

1Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, 2 Wanglang Road, Bangkoknoi, Bangkok, 10700 Thailand

2Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Corresponding author.

Received 2018 Aug 1; Accepted 2018 Nov 16.

Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (

http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Abstract

Background

Vitamin D has been reported to be associated with many allergic diseases. There are a limited number of the studies of vitamin D supplementation in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). This study aims to study the relationship between vitamin D and CSU in terms of serum vitamin D levels, and the outcomes of vitamin D supplementation.

Methods

A literature search of electronic databases for all relevant articles published between 1966 and 2018 was performed. The systematic literature review was done following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis recommendations.

Results

Seventeen eligible studies were included. Fourteen (1321 CSU cases and 6100 controls) were concerned with serum vitamin D levels in CSU patients. Twelve studies showed statistically significant lower serum vitamin D levels in CSU patients than the controls. Vitamin D deficiency was reported more commonly for CSU patients (34.389.7%) than controls (0.068.9%) in 6 studies. Seven studies concerned with vitamin D supplementation in CSU patients showed disease improvement after high-dosages of vitamin D supplementation.

Conclusion

CSU patients had significantly lower serum vitamin D levels than the controls in most studies. However, the results did not prove causation, and the mechanisms were not clearly explained. Despite the scarcity of available studies, this systematic review showed that a high dosage of vitamin D supplementation for 412weeks might help to decrease the disease activity in some CSU patients. Well-designed randomized placebo-controlled studies are needed to determine the cut-off levels of vitamin D for supplementation and treatment outcomes.

Background

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is defined as the occurrence of spontaneous wheals, angioedema, or both for more than 6weeks [1]. Recommended first-line treatment is modern, second-generation H1-antihistamines. For refractory patients, a short course of systemic corticosteroids, omalizumab or ciclosporin is recommended [1].

Vitamin D, a fat-soluble vitamin, exists in two forms: D2 (ergocalciferol) and D3 (cholecalciferol) [2]. The human body gains it from the diet and sunlight. Vitamin D2 has been found in some mushrooms, e.g., shiitake mushrooms and button mushrooms. Vitamin D3 is commonly found in halibut, mackerel, eel, salmon, beef liver, and egg yolks [3]. Within the human body, only the skin can produce vitamin D3. Ultraviolet B radiation (wavelength, 290315nm) converts 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin to previtamin D3, which is rapidly converted to vitamin D3. Vitamins D2 and D3 from diets and vitamin D3 from skin photobiosynthesis are initially metabolized by the liver enzyme 25-hydroxylase (CYP2R1) to 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), the major circulating metabolite which is commonly used for evaluation of vitamin D status. The 25(OH)D is metabolized in the kidneys by the enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D), the most biologically active form of vitamin D [2].

Vitamin D plays a major role in mineral homeostasis [2]. Besides its role in bone physiology, it also has a role on cutaneous immunity by binding to its nuclear receptors and plasma membrane receptors of epithelial cells, and to various cells such as mast cells, monocytes, macrophages, T-cells, B-cells, and dendritic cells [4, 5]. In the innate immune system, vitamin D contributes to improving antimicrobial defenses by stimulating the expression of antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidin and human -defensin [6]. In the adaptive immune system, in vitro study showed that physiologic (in vivo) concentration of 25(OH)D3 in serum-free medium can activate T cells to express CYP27B1 and then convert 25(OH)D3 to 1,25(OH)2D3. (active form of vitamin D) [7]. Vitamin D can suppress dendritic cell maturation and inhibits Th1 cell proliferation by decreasing Th1 cytokine secretion. It also induces hyporesponsiveness by blocking proinflammatory Th17 cytokine secretion and decreasing interleukin (IL)-2 production from regulatory T (Treg) cells. It inhibits B-lymphocyte function resulting in the reduction of immunoglobulin E production [8, 9]. Moreover, vitamin D has influences on the proliferation, survival, differentiation, and function of mast cells [5, 10].

The vitamin D binding protein (VDBP) and vitamin D receptor (VDR) are two proteins that influence the biological actions. VDBP is the main carrier protein in the circulation. Group-specific component (GC) is the gene that encodes VDBP [11]. Genetic polymorphism in the GC gene influences the concentration of VDBP and its affinity for vitamin D. Regarding VDR, the binding of VDR to vitamin D results in epigenetic modification and transcription of various specific genes [12]. The human VDR gene is located in chromosome 12. Polymorphism in the VDR gene has been shown to alter VDR functions that affect vitamin D activities [13]. Among the VDR polymorphisms, the SNPs rs1544410 and rs2228570 are frequently studied in association with allergic diseases. However, NasiriKalmarzi et al. reported no significant correlation between the VDR rs2228570 and VDBP rs7041 SNPs and the development of chronic urticaria (CU), although they found a positive correlation between serum VDBP and the progression of CU. They concluded that alteration of the vitamin D pathway at the gene and protein levels may be a risk factor for the progression of CU [14].

There have been reports of an association between vitamin D and allergic diseases, such as food allergies, rhinosinusitis, recurrent wheeze, asthma, atopic dermatitis, and CSU [1517]. Some studies have shown that vitamin D is involved in the etiopathogenesis of CSU, while other studies have demonstrated clinical improvement in CSU with vitamin D supplements. However, there are a limited number of studies on this issue, and their results are inconsistent. [14, 1833].

We performed a systematic review to examine the serum vitamin D levels in patients with CSU. Data concerning vitamin D supplementation in the CSU patients were also studied to determine whether supplementation impacts treatment outcomes.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This systematic review adhered to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis recommendations (PRISMA).

A literature search of electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library, and CINAHL) for all relevant articles published between Jan 1, 1966, and September 30, 2018 was conducted using the search term chronic urticaria and vitamin D or 25(OH)D insufficiency or deficiency or 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency The titles and abstracts of the articles identified in the search were screened by two independent reviewers (KK and SA) for eligibility based on the inclusion criterion. Full texts were then obtained and assessed for eligibility by those two reviewers (KK and SA). A further manual search of the references cited in the selected articles was subsequently performed to identify any relevant studies that might have been missed in the initial search. Finally, all yielded relevant reports were systematically reviewed (Fig.).

Flow diagram of literature review in this study. Seventeen studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in our systematic review. *Of the 14 studies, the relation between serum vitamin D level and CSU were assessed [14, 18, 2025, 2833]. In 7 studies, various severity assessment were used to evaluate the effect of vitamin D supplementation in CSU patients [19, 2427, 31, 32]. CSU chronic spontaneous urticaria

Any types of publication involving vitamin D in CSU patients were included in our systemic review. The exclusion criteria were: (1) articles that were not published in English; (2) duplicated publications; (3) studies published only in abstract form; and (4) continuous medical education (CME) and review articles.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two investigators (KK and SA) assessed the risk of bias of the eligible studies included in this systematic review. We used Cochrane Collaborations tool to assess the risk of bias in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was used to assess the risk of bias in non-RCT studies.

Data extraction for serum vitamin D levels and CSU

The search strategies were mainly used to identify vitamin D levels, and to compare the levels found in CSU patients and controls. Serum vitamin D levels are mostly reported in the form 25(OH)D. After the eligible full-text articles were reviewed and the relevant data reported in those articles were further searched, the following information was extracted from each: the first author, year of publication, type of study, number and characteristics of the population, number of cases and controls, method of vitamin D measurement, type (form) and unit of the measured serum vitamin D, vitamin D levels in case and control groups, and study outcomes. Information was completely and carefully extracted from the eligible articles.

Data extraction for treatment or supplementation of vitamin D

We also examined whether vitamin D supplementation has an impact on the outcomes of urticaria treatment. All relevant data were extracted, namely, the first author, year of publication, type of study, number and characteristics of cases and/or controls, form, dosage and duration of vitamin D treatment, assessment duration, methods and parameters for outcome measurement, vitamin D status at baseline and after vitamin D treatment, and treatment outcomes.

Results

Literature search

The detailed steps of the literature search are illustrated in the flow chart at Fig.. A total of 140 potentially relevant studies were found. The titles and abstracts of these articles were reviewed. Of the 117 excluded studies, 42 were removed due to duplication and 75 were irrelevant; the remainder (23 studies) were screened for full text review. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 5 review articles were excluded, and 1 study was excluded because it had not been published in English. The full texts of the remaining 17 studies were extensively reviewed, and all were finally included [14, 1833].

Characteristics of included studies

The 17 studies were published during the period 20102018 [14, 1833]. The main characteristics of the studies were summarized into two issues: serum vitamin D levels in CSU patients, and outcomes of vitamin D supplementation in CSU patients.

Risk of bias

Three RCTs in our systematic review were estimated mainly at low risk. The majority of the non-RCT studies had a low risk of bias according to ROBIN-I assessment.

Serum vitamin D levels in CSU patients

Fourteen studies were concerned with serum vitamin D levels in CSU patients. There were 1 RCT [32], 3 cross-sectional studies [20, 22, 33], 8 casecontrol studies [14, 18, 21, 2325, 28, 31], and 2 retrospective reviews [29, 30] (Table). All studies drew upon data from a total of 7421 participants, with 1321 patients with CSU and 6100 controls, including 5456 healthy controls, and 25 cases of allergic rhinitis controls. The remaining 619 participants were 593 acute urticaria patients and 26 atopic dermatitis patients. Statistical analyses for meta-analysis were not performed due to the substantial heterogeneity of the reported data.

Table1

Serum vitamin D levels in CSU patients

| Study, year | Study size/population | Vitamin D data | Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | Units | Serum 25(OH)D levels | ||||||

| CSU | Controls | |||||||

| Cross-sectional study | ||||||||

| Chandrashekar et al. [20] | 45 CSU45 age-, sex-matched healthy controls | ELISA kit(Euroimmun AG, Lubeck, Germany) | ng/mL | 12.72.7(meanSD) | 24.313.5(meanSD)(p<0.0001) | Significant lower vitamin D levels among chronic urticaria patients and controlsSignificant lower vitamin D levels in APST positive group (11.12.1ng/mL) compared with APST negative group (15.11.3ng/mL) (p<0.0001)Significant negative correlation between vitamin D levels and USS, IL-17, TGF-1 and ESR (p<0.0001) | ||

| Lee et al. [22] | 57 CSU567 acute urticaria3159 controls | ND | ng/mL | 22.94.9(meanSD) | Acute urticaria; 20.55.1(meanSD)(p=0.069)Controls; 20.05.1(meanSD)(p=0.124) | The study was conducted in childrenNo significant difference in the 25(OH)D levels between CSU patients and acute urticaria patients and controls (p=0.183) | ||

| Rather et al. [33] | 110 CSU110 age-, sex-matched healthy controls | Chemiluminescence method/kit method (Siemens, USA) | ng/mL | 19.66.9(meanSD) | 38.56.7(meanSD)(p<0.001) | Significant lower vitamin D levels in CSU patients compared with controlsSignificant negative correlation between serum vitamin D level and UAS (p<0.001)Significant lower vitamin D levels in CSU patients with the ASST positive subjects than in the ASST negative subjects (p<0.001)No significant correlation between vitamin D level and duration of the disease | ||

| Casecontrol study | ||||||||

| Thorp et al. [28] | 25 CSU25 allergic rhinitis controls | ND | ng/mL | 29.413.4(meanSD) | 39.614.7(meanSD)(p=0.016) | Significantly reduced vitamin D levels in CSU patients compared with controlsNo correlation of vitamin D levels and duration, severity of disease, ASST or thyroid autoantibody testingNo significant difference in the proportion of vitamin D deficiency between CSU groups and controls | ||

| Vitamin D status | ||||||||

| Vitamin D deficiency (<30ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 48% (12/25) | 28% (7/25)(p=0.24) | |||||||

| Abdel-Rehim et al. [18] | 22 CSU20 age- and sex-matched controlsDisease severity8 (36.4%): moderate urticaria(UAS7=1627)14 (63.6%): severe urticaria(UAS7=2842) | ELISA kit (Immundiagnostik AG,Bensheim, Germany) | nmol/L | 28.49.09(meanSD) | 104.576.8(meanSD)(p<0.01) | Significantly lower vitamin D levels among patients in comparison to controlsNegative correlation between vitamin D levels and IgE levels (r=0.45, p<0.05)No association between vitamin D levels and duration and the severity of the disease | ||

| Grzanka et al. [21] | 35 CSU33 age-, sex- and BMI (<30) matched healthy controls | An automated direct electrochemiluminescenceimmunoassay(Elecsys, Roche Diagnostic, Mannheim Germany) | ng/mL | 26.0(median) | 31.1(median)(p=0.017) | Significantly lower serum 25(OH)D concentration in CSU group compared with the control subjectsNo significant differences in serum 25(OH)D concentration between the mild and moderate-severe symptoms patientsSlightly significantly lower 25(OH)D concentrations in moderate-severe CSU than those of the controls (22.6 vs 31.1ng/mL, p=0.048)No significant difference in vitamin D levels between mild CSU and healthy control subjectsSignificantly higher proportion of vitamin D deficiency (<20ng/mL) in patients with CSU than in the normal populationNo significant difference in the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency (2029ng/mL) between CSU patients and the normal subjectsNo significant correlations between serum concentration of CRP and 25(OH)D levelsNo significant difference in serum 25(OH) concentrations and ASST testing | ||

| Vitamin D status | ||||||||

| Vitamin D insufficiency (20<30ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 31.4% (11/35) | 39.4% (13/33)(p=0.41) | |||||||

| Vitamin D deficiency (<20ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 31.4% (11/35) | 6% (2/33)(p=0.025) | |||||||

| Severe vitamin D deficiency (<10ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 2.9% (1/35) | 0% (0/33)(p=0.52) | |||||||

| Movahedi et al. [23] | 114 CSU187 sex- and age-matched healthy controls | Enzyme immunoassay method (EIA) (Immunodiagnostic system; IDS (LTD), UK) | ng/mL | 15.81.5 | 22.61.6(p=0.005) | Significantly lower serum 25(OH)D concentration in CSU group compared to healthy subjectsNo significant differences in vitamin D levels between autoimmune chronic urticaria patients and the control group (p=0.11)Significant association between vitamin D deficiency and increased susceptibility to CSU (p=0.001)A 2.4-fold (95% CI 1.44) risk of having CSU in individuals with vitamin D deficiency (<20ng/ml)Significantly lower levels of vitamin D in patients with longer duration of urticaria symptoms (>24h) (p=0.046)A significant positive correlation between vitamin D levels and UAS (r=0.2, p=0.042)No significant relationship between IgE levels and vitamin D levels | ||

| Vitamin D status | ||||||||

| Vitamin D sufficiency | ||||||||

| 8.8% (10/114) | 26.2% (49/187) | |||||||

| Vitamin D insufficiency (2030ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 15.8% (18/114) | 16.6% (31/187) | |||||||

| Vitamin D deficiency (<20ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 75.4% (86/114) | 57.2% (107/187) | |||||||

| Rasool et al. [25](Randomizedcasecontrol) | 147 moderate-severe CSU130 healthy controls | Enzyme immunoassay | ng/mL | 17.871.22(meanSEM) | 27.651.65(meanSEM)(p<0.0001) | Low serum 25(OH)D levels in 91% of CSU patients and 64% of the healthy subjectsSignificantly lower vitamin D levels in CSU patients compared with controls | ||

| Vitamin D status | ||||||||

| Vitamin D insufficiency (2030ng/mL)or Vitamin D deficiency (1020ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 91.3% | 63.84%(p<0.0001) | |||||||

| Boonpiyathad et al. [31](Prospectivecasecontrol) | 60 CSU40 healthy controls | ND | ng/mL | 15.0 (752)median (minmax) | 30.0 (2546)median (minmax)(p<0.001) | Significantly lower the median 25(OH)D concentration in the CSU group than the control groupSignificantly higher patients with vitamin D deficiency (<20ng/mL) in the CSU group than the control group (p<0.001)No association between UAS7 and DLQI scores with 25(OH)D levelsSignificant correlation between ESR and vitamin D levels (p=0.001) | ||

| Vitamin D status | ||||||||

| Vitamin D insufficiency (>20<30ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 28% | 45%(p=0.38) | |||||||

| Vitamin D deficiency (<20ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 55% | 0%(p<0.001) | |||||||

| Oguz Topal et al. [24](Prospectivecasecontrol) | 58 CSU45 healthy age-matched controlsDisease severity3 (5.2%): mild urticaria(UAS4a: 08)15 (25.8%): moderate urticaria(UAS4: 916)40 (68.9%): severe urticaria(UAS4: 1724) | An automated direct electrochemiluminescence immunoassay(Elecsys, Roche Diagnostic, Mannheim, Germany) | ug/L | All CSU8.45 (1.152.5)median (minmax)(p<0.001)Mild-moderate CSU8.95 (3.923.0)median (minmax)(p=0.011)Severe CSU7.1 (1.152.5)median (minmax)(p<0.001) | 15.3 (3.161.0)median (minmax) | Significantly lower serum 25(OH)D concentration in total CSU group, mild-moderate CSU group and severe CSU group compared to healthy subjectsSignificantly higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in CSU patientsNo significant differences in 25(OH)D levels between CSU patients with mild-moderate symptoms and severe symptomsNo significant differences between vitamin D-deficient or insufficient group regarding CU-Q2oL and UAS4 scores (p>0.001)No association between the anti-TG and the anti-TPO autoantibodies and the levels of vitamin D in CSU patients, (p=0.641 and p=0.373, respectively)No association between the prevalence of high levels of total IgE and the levels of vitamin D in CSU patients (p=0.5) | ||

| Vitamin D status | ||||||||

| Vitamin D insufficiency (<30g/L) | ||||||||

| 98.3% (57/58) | 86.7% (39/45)(p=0.041) | |||||||

| Vitamin D deficiency (<20g/L) | ||||||||

| 89.7% (52/58) | 68.9% (31/45)(p=0.017) | |||||||

| Nasiri-Kalmarzi et al. [14] | 110 CSU110 healthy controls | Specific E LISA(Monobind Inc., Lake Forest, CA, USA) | ng/mL | 19.261.26(meanSEM) | 31.727.14(meanSEM)(p=0.006) | Significantly lower serum vitamin D levels in chronic urticaria patients compared to controlsSignificantly association between decreased levels of serum vitamin and increased susceptibility to chronic urticaria (p=0.027)Significant negative correlation between vitamin D levels with ASST and UAS (p<0.001 and p=0.001, respectively)No significant correlation between vitamin D levels and serum total IgE (p=0.083)Higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency in chronic urticaria patientsNo significant correlation between vitamin D levels and total IgE levels | ||

| Vitamin D status | ||||||||

| Vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency | ||||||||

| 58.02% | 48.89% | |||||||

| Randomized controlled trial | ||||||||

| Dabas et al. [32] | 241CSU184 healthy controls | ND | nmol/L | 17.4713.36(meanSD) | 22.0914.06(meanSD)(p=0.002) | Significantly lower vitamin D level were in CSU patients than in healthy controlsNo correlation between vitamin D deficiency and sex, ASST, APST, serum IgE, angioedema or disease duration | ||

| Vitamin D status | ||||||||

| Vitamin D sufficiency (>30ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 20.91% (23/110) | 64.54% (71/110) | |||||||

| Vitamin D insufficiency (2030ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 15.45% (17/110) | 21.82% (24/110) | |||||||

| Vitamin D deficiency (<20ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 63.64% (70/110) | 13.64% (15/110) | |||||||

| Retrospective study | ||||||||

| Woo et al. [29] | 72 CSU26 acute urticaria26 atopic dermatitis72 healthy controls | ND | ng/mLb | CSU | Acute urticaria | Atopic dermatitis | Healthy controls | Both children and adults were enrolledSignificantly lower serum 25(OH)D3 levels in CSU group compared to those in the other groupsSignificantly higher proportion of patients with critically low vitamin D levels (<10ng/mL) in the CSU group than in acute urticaria, atopic dermatitis, and healthy controlsSignificant negative associations between the vitamin D levels and urticaria activity score and disease duration (p<0.001, p=0.008, respectively)Significantly more critically low vitamin D status in the moderate/severe UAS group than in the mild UAS group (p=0.03)Significantly lower serum vitamin D levels in subjects with a positive ASST than in subjects with a negative resultSignificantly higher number of patients with critically low vitamin D in the moderate/severe UAS group than in the mild UAS group (p=0.03)Significantly lower vitamin D levels in the ASST positive subjects (9.124.25ng/mL) than in the ASST negative subjects (13.337.09ng/mL) (p=0.034)Significantly higher proportion of those with critically low vitamin D status in the ASST positive group (60%) than in the ASST negative group (32%) (p=0.021) |

| 11.867.16(meanSD) | 14.125.56(meanSD)(p=0.024) | 16.128.09(meanSD)(p=0.008) | 20.779.74(meanSD)(p<0.001) | |||||

| Vitamin D status | ||||||||

| Sufficiency (30ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 2% (2/72) | 0% | 2% | 20% (15/72) | |||||

| Insufficiency (between 20 and 29ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 10% (7/72) | 11% | 24% | 27% (20/72) | |||||

| Deficiency (<20ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 39% (28/72) | 63% | 46% | 45% (32/72) | |||||

| Critically low (<10ng/mL) | ||||||||

| 49% (35/72) | 26% (6/26)(p<0.002) | 28% (7/26)(p<0.004) | 8% (5/72)(p<0.001) | |||||

| Wu et al. [30] | 225 CSU1321 healthy controls | ND | nmol/L | CSU | Controls | Significantly higher vitamin D levels in CSU patients than the general population | ||

| 51.427.03(meanSD) | 45.424.84(meanSD)(p=0.001) |

The methods used for the measurement of vitamin D varied among the studies (Table). All of the studies reported the serum vitamin D level as 25(OH)D except two: one study by Woo et al. [29], which measured 25(OH)D3, and NasiriKalmarzis study, which did not report the type of vitamin D measured [14]. The units of serum 25(OH)D were reported mainly in ng/mL [14, 2023, 25, 28, 29, 31, 33], but some studies reported them in g/L [24] and nmol/L [18, 30, 32].

The main outcomes of the serum vitamin D levels in the CSU patients compared to the controls are summarized at Table. Twelve studies showed statistically significantly lower levels of serum vitamin D in the CSU patients than the controls [14, 18, 20, 21, 2325, 28, 29, 31, 33]. Wu et al. showed significantly higher levels of serum vitamin D in the CSU patients [30]. They compared the serum vitamin D levels of CSU patients in Southampton General Hospital to those of the general United Kingdom (UK) population (data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey). The serum vitamin D levels of the 225 CSU patients were significantly higher than those of the 1321 UK population (control group). Lee et al. conducted a cross-sectional, population-based study of Korean children (aged 413years; 3159 were controls; 624 had current urticaria, of which 57 were CSU and 567 acute urticaria). There was no statistically significant difference in the serum vitamin D levels of the CSU patients and the controls (p=0.124) [22].

Table2

Summary of parameters of vitamin D in CSU

| Outcome measurement | Pro | Cons | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower serum vitamin D levels in CSU patients than healthy controls | One study showed significantly higher levels of vitamin D in CSU patients than that of controls | Wu et al. [30] | ||

| One study showed no significant difference in vitamin D levels between CSU patients and that of controls | Lee et al. [22] | |||

| Twelve studies showed significant lower levels of vitamin D in CSU patients than that of controls | Thorp et al. [28]Grzanka et al. [21]Chandrashekar et al. [20]Abdel-Rehim et al. [18]Movahedi et al. [23]Woo et al. [29]Rasool et al. [25]Boonpiyathad et al. [31]Oguz Topal et al. [24]Nasiri-Kalmarzi et al. [14]Dabas et al. [32]Rather et al. [33] | |||

| Vitamin D insufficiency in CSU patients more than in controls | One study showed significantly higher prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in controls than in CSU | Movahedi et al. [23] | ||

| Two studies showed no significant difference in the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency between CSU patients and controls | Grzanka et al. [21]Boonpiyathad et al. [22] [31] | |||

| One study showed significant difference in the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency between CSU patients and controls | Oguz Topal et al. [24] | |||

| Vitamin D deficiency in CSU patients more than in controls | One study showed no significant difference in the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency between CSU patients and controls | Thorp et al. [28] | ||

| Three studies showed significant difference in the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency between CSU patients and controls | Grzanka et al. [21]Boonpiyathad et al. [31]Oguz Topal et al. [24] | |||

| One study show significant difference in the proportion of critically low vitamin D levels in the CSU patients and in acute urticaria, atopic dermatitis, and healthy controls | Woo et al. [29] | |||

| Lower serum vitamin D levels between CSU and acute urticaria | One study showed no significant difference levels of vitamin D between CSU and acute urticaria patients | Lee et al. [22] | ||

| One study showed significantly lower levels of vitamin D in CSU than acute urticaria patients | Woo et al. [29] | |||

| Lower serum vitamin D levels between CSU and atopic dermatitis | One study showed significantly lower levels of vitamin D in CSU than atopic dermatitis | Woo et al. [29] | ||

| Lower serum vitamin D levels between CSU and allergic rhinitis | One study showed significantly lower levels of vitamin D in CSU than allergic rhinitis | Thorp et al. [28] | ||

| Low serum vitamin D levels and higher disease activity | One study reported a significant positive correlation between vitamin D levels and urticaria activity score | Movahedi et al. [23] | ||

| Six studies reported no association | Thorp et al. [28]Abdel-Rehim et al. [18]Grzanka et al. [21]Rorie et al. [26]Boonpiyathad et al. [31]Oguz Topal et al. [24] | |||

| Three study reported significant negative association between vitamin D levels and urticaria activity scoreOne study reported significant negative association between vitamin D levels and urticaria severity score | Woo et al. [29]Nasiri-Kalmarzi et al. [14]Rather et al. [33]Chandrashekar et al. [20] | |||

| Low serum vitamin D levels and longer disease duration | Five studies reported no association | Thorp et al. [28]Abdel-Rehim et al. [18]Grzanka et al. [21]Dabas et al. [32]Rather et al. [33] | ||

| One studies reported significant negative association | Woo et al. [29] | |||

| Low serum vitamin D levels and high ESR | Two study reported significant correlation | Chandrashekar et al. [20]Boonpiyathad et al. [31] | ||

| Low serum vitamin D levels and high CRP levels | One study reported no association | Grzanka et al. [21] | ||

| Low serum vitamin D levels and high IgE levels | One study reported negative association | Abdel-Rehim et al. [18] | ||

| Four studies reported no association | Movahedi et al. [23]Oguz Topal et al. [24]Nasiri-Kalmarzi et al. [14]Dabas et al. [32] | |||

| Low serum vitamin D levels and high IL-17 levels | One study reported negative association. | Chandrashekar et al. [20] | ||

| Low serum vitamin D levels and TGF-1 | One study reported negative association | Chandrashekar et al. [20] | ||

| Low serum vitamin D levels and thyroid autoantibodies testing | Two studies reported no association | Thorp et al. [28]Oguz Topal et al. [24] | ||

| Low serum vitamin D levels and a positive ASST or APST | One study reported significant lower levels of vitamin D in patients with a positive APST | Chandrashekar et al. [20] | ||

| Three study reported significant lower levels of vitamin D in patients with a positive ASST. | Woo et al. [29]Nasiri-Kalmarzi et al. [14]Rather et al. [33] | |||

| Three studies reported no association between the ASST-positive and ASST-negative groups | Thorp et al. [28]Grzanka et al. [21]Dabas et al. [32] |

Degree of severity of serum vitamin D levels in CSU patients

The serum vitamin D levels were categorized into subgroups according to the vitamin D status. Serum 25(OH)D levels of >30ng/mL, 2030ng/mL, and <20ng/mL were defined as sufficiency, insufficiency, and deficiency, respectively; levels of<10ng/mL indicated a critically low or severe deficiency. The cut-point values to define vitamin D status in each study were very similar even though slightly different values were found in some studies (Table). The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was reported more commonly in the CSU patients (34.389.7%) than in the controls (0.068.9%) in 8 studies [21, 23, 24, 28, 29, 3133]. Four of those studies reported statistically significant differences [21, 24, 29, 31].

Table3

Comparison of reported degree severity of serum vitamin D levels in CSU patients and controls

| Studies | Thorp et al. [28] | Chandrashekar et al. [20] | Grzanka et al. [21] | Movahedi et al. [23] | Woo et al. [29] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Allergic rhinitiscontrols | Cases | Healthy controls | Cases | Healthycontrols | Cases | Healthy controls | Cases | Healthy controls | |

| N | 25 | 25 | 45 | 45 | 35 | 33 | 114 | 187 | 72 | 72 |

| Vitamin D levels | 29.4(mean) | 39.6(mean) | 12.72.7 | 24.313.5 | 26.0(median) | 31.1(median) | 15.8 | 22.6 | 11.86(mean) | 20.77(mean) |

| Sufficiency | ND | ND | ND | 11/45(24.44%) | ND | ND | 10(8.8%) | 49(26.2%) | 2(2%) | 15(20%) |

| Insufficiency | ND | ND | ND | 18/45(40%) | 11(31.4%) | 13(39.4%) | 18*(15.8%) | 31(16.6%) | 7(10%) | 20(27%) |

| Deficiency | 12(48%) | 7(28%) | ND | 16/45(35.55%) | 11*(31.4%) | 2(6%) | 86(75.4%) | 107(57.2%) | 28(39%) | 32(45%) |

| Severe deficiency | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1(2.9%) | 0(0%) | ND | ND | 35*(49%) | 5(8%) |

| Definition | ||||||||||

| Sufficiency | ND | >30ng/mL | 30ng/mL | ND | 30ng/mL | |||||

| Insufficiency | ND | Between 20 and 30ng/mL | 20<30ng/mL | 2030ng/mL | Between 20 and 29ng/mL | |||||

| Deficiency | <30ng/mL | <20ng/mL | <20ng/mL | <20ng/mL | <20ng/mL | |||||

| Critically low/Severe deficiency | ND | ND | <10ng/mL | ND | <10ng/mL |

| Studies | Rasool et al. [25] | Boonpiyathad et al. [31] | Oguz Topal et al. [24] | Nasiri-Kalmarzi et al. [14] | Rather et al. [33] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Healthycontrols | Cases | Healthy controls | Cases | Healthy controls | Case | Healthy controls | Case | Controls | |

| N | 147 | 130 | 60 | 40 | 58 | 45 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 |

| Vitamin D levels | 17.87(mean) | 27.65(mean) | 15.0(median) | 30.0(median) | 8.45(median) | 15.3(median) | 19.261.26(mean) | 31.727.14(mean) | 19.66.9(mean) | 38.56.7(mean) |

| Sufficiency | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 23(20.91%) | 71(64.54%) |

| Insufficiency | 91.3% | 63.84% | 28% | 45% | 57*(98.3%) | 39(86.7%) | 58.02% | 48.89% | 17(15.45%) | 24(21.82%) |

| Deficiency | 55%* | 0% | 52*(89.7%) | 31(68.9%) | 70(63.64%) | 15(13.64%) | ||||

| Severe deficiency | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Definition | ||||||||||

| Sufficiency | >30ng/mL | ND | >30g/L | ND | >30ng/mL | |||||

| Insufficiency | 2030ng/mL | >20<30ng/mL | <30g/L | ND | 2030ng/mL | |||||

| Deficiency | 10<20ng/mL | <20ng/mL | <20g/L | ND | <20ng/mL | |||||

| Critically low/Severe deficiency | <10ng/mL | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Other effects of vitamin D on CSU

The effects of vitamin D on CSU are summarized at Table. The studies also compared the serum vitamin D levels of the CSU patients with those of patients with other diseases, such as acute urticaria [22, 29], atopic dermatitis [29], and allergic rhinitis [28]. Vitamin D level was significantly lower in CSU patients than in atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis [28, 29]. Four out of 11 studies reported significant association between low serum vitamin D levels and high disease activity whereas seven studies did not find this significant association. Most studies demonstrated that there was no association between low serum vitamin D levels and disease duration [18, 21, 28, 32, 33]. Others reported a relationship between the serum vitamin D levels and other investigations, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate [20, 31], C-reactive protein [21], serum IgE [14, 18, 23, 24, 32], IL-17 [20], transforming growth factor-1 [20], thyroid autoantibodies [24, 28], autologous serum skin test [14, 21, 28, 29, 33], and autologous plasma skin test [20]. It was shown that low serum vitamin D level was significantly associated with high levels of ESR, IgE, IL-17, and transforming growth factor-1 [18, 20, 31].

Outcome of vitamin D supplementation on CSU patients

Seven studies (2 RCTs [26, 32], 3 casecontrol studies [24, 25, 31], 1 prospective study [19], and 1 case report [27]) were concerned with vitamin D supplementation in 587 CSU patients. The outcomes of the vitamin D supplementation were compared to baseline in 6 studies [19, 2427, 32] and to controls in 1 study [31].

The regimens of vitamin D supplementation in each study were reviewed and are summarized at Table. Four studies used vitamin D3 at dosages ranging from 2800 to 75,000IU/week [2427], one study used vitamin D2 at a dosage of 140,000IU/week [31], and another study did not define the form of vitamin D administered at a dosage of 50,000IU/week [19]. Similarly, the form of vitamin D supplementation was also not defined in the RCT study but patients were categorized into three groups to receive low-dose (2000IU/d), high-dose (60,000IU/week), and without vitamin D supplementation, respectively [32]. The duration of the vitamin D supplementations ranged from 4 to 12weeks. The serum vitamin D levels were evaluated in 4 studies and were reported as 25(OH)D [2527, 31].

Table4

Outcome of vitamin D supplement in CSU patients

| Study, year | Study design | N | Enroll | Concomitant medications | Intervention(Dose, type, duration,source) | Duration | Main outcome measurement | Vitamin D status (ng/mL) | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | End of treatment | |||||||||

| Sindher et al. [27] | Case report | 1 | Chronic urticaria | Calcium citrate 800mg/dayFexofenadineAluminium/magnesium antacid | Vitamin D3 (Cholecalciferol 400IU/day | 8weeks | ND | 4.7 | ND | Continued to have intermittent urticaria |

| Then increased to 2000IU/day) | ND | ND | 65 | Complete resolution without antihistamine | ||||||

| Rorie et al. [26] | Prospective,double-blinded, randomized controlled trial(single-center clinical study) | 42 | CSU receiving high dose vitamin D3 (4000IU/day) supplementation(n=21) | CetirizineRanitidineMontelukastUse for intolerable or uncontrolled symptomsPrednisoloneHydroxychloroquine | Vitamin D3 4,000IU/day | 12weeks | USS | Vitamin D status(meanSE) | Decrease total USS scores(meanSE) | |

| 28.82.2 | 56.03.9 | 15.02.9(p=0.02) | ||||||||

| CSU receiving low dose vitamin D3 (600IU/day) supplementation(n=21) | Vitamin D3 600IU/day | 37.13.4 | 35.82.3 | 24.14.0 | ||||||

| Significant decrease in total USS score in the high, but not low, vitamin D3 treatment group by week 12 (p=0.02)No correlation between 25(OH)D levels and USS score at baseline (r=0.07, p=0.65) or at week 12 (r=0.13, p=0.45)The high vitamin D3 treatment group showed a decreased total USS score compared with the low vitamin D3 treatment group, but this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.052)Subjects in the high vitamin D3 treatment group reported decrease body distribution of hives on an average day (p=0.033), decrease body distribution of hives on the worst day (p=0.0085), and decrease number of days with hives (p=0.03) compared with subjects in the low vitamin D3 treatment group. |

| Study, year | Study design | N | Enroll | Concomitantmedications | Intervention (Dose, type, duration, source) | Duration | Main outcome measurement | Vitamin D status(ng/mL) | Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | End of treatment | ||||||||||

| Rasool et al. [25] | Randomized casecontrol study | 147 | CSUAny vitamin D levels (serum 25(OH)D) fromGroup 1Severe deficiencyVitamin D levels<10ng/mLGroup 2Deficient levelsVitamin D levels10<20ng/mLGroup 3Insufficient levelsVitamin D levels2030ng/mLGroup 4Sufficient levelsVitamin D levels>30ng/mL)Then randomized toSub-group A (n=48)sub-group B(n=42)Sub-group C (n=57) | 6weeks | VAS5-D itch score | Vitamin D status(meanSEM) | VAS score(meanSEM) | 5-D itch score(mean) | |||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | ||||||

| Sub-group A | Sub-group A | Sub-group A | Sub-group A | ||||||||

| None | Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) 60,000IU/week for 4weeks | 16.981.43 | 56.743.76(p<0 .0001) | 6.70.043 | 5.20.70(p=0.0088) | 14.50.72 | 12.061.10(p=0.0072) | ||||

| Sub-group B | Sub-group B | Sub-group B | Sub-group B | ||||||||

| Hydroxyzine25mg/day for 6weeksCorticosteroids(deflazacort)6mg/day for 6weeks | None | 17.041.54 | 16.441.50 | 6.60.42 | 3.30.50(p<0.0001) | 13.90.77 | 8.11.13(p<0.001) | ||||

| Sub-group C | Sub-group C | Sub-group C | Sub-group C | ||||||||

| Hydroxyzine25mg/day for 6weeksCorticosteroids6mg/day for 6weeks | Vitamin D3 60,000IU/week for 4weeks | 18.951.42 | 41.732.85 (p<0.0001) | 6.680.40 | 1.860.39(p<0.0001) | 13.90.68 | 5.010.94(<0.0001) | ||||

| Significantly decreased in VAS in every groupsSignificantly decreased in 5D itch score in every groupsImprovement in the CSU symptoms in patients with vitamin D3 as monotherapyBetter improvement of symptoms and quality of life in combinatorial therapy group than standard therapeutic regimen groupSignificant difference in VAS in subgroup A compared to subgroup B and C (p=0.016 and p<0.0001, respectively)Significant difference in VAS in subgroup C compare to subgroup B (p=0.0203)Significant difference in 5-D score in subgroup A compared to subgroup B and C (p=0.0116 and p<0.0001, respectively)Significant difference in 5-D score in subgroup C compared to subgroup B (p=0.0382) | |||||||||||

| 130 | Healthy control | None | None | 6weeks | Vitamin D levels | Group 1 | No change in serum 25(OH)D levels | ||||

| 7.3100.52 | 5.8990.28 | ||||||||||

| Group 2 | |||||||||||

| 15.260.47 | 16.961.26 | ||||||||||

| Group 3 | |||||||||||

| 23.980.46 | 23.150.95 | ||||||||||

| Group 4 | |||||||||||

| 47.782.23 | 49.182.97 | ||||||||||

| Oguz Topal et al. [24] | Prospective casecontrol study | 57cases | CSUSerum 25(OH)D<30ug/L | None | Vitamin D3 300,000IU/month | 12weeks | UAS4CU-Q2oL | ND | ND | UAS4(median(minmax)) | CU-Q2oL(median(minmax)) |

| Before | After | Before | After | ||||||||

| 21(042.0) | 6(021.0)(p<0.001) | 38(6.5115.2) | 10.8(043.4)(p<0.001) | ||||||||

| Significant improvements in UAS4 and CU-Q2oL | |||||||||||

| Boonpiyathad et al. [31] | Prospective casecontrol study | 50cases | CSUSerum 25(OH)D<30ng/mL(vitamin D supplement group) | Non-sedative antihistamine | Ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) 20,000IU/day | 6weeks | UAS7DLQI | 13 (829) median (minmax) | 40 (2862) median (minmax) | UAS7 | DLQI scores |

| Before | After | Before | After | ||||||||

| 27(638) | 15(233) | 13(431) | 6(120) | ||||||||

| 10 controls | CSUSerum 25(OH)D30ng/ml(non-vitamin D supplement group) | ND | None | 6weeks | UAS7DLQI | 37 (3352)median(minmax) | 38 (3352)median(minmax) | 26(1842) | 26(1644) | 12(528) | 14(327) |

| Significant improvements in UAS7 and DLQI scores in the vitamin D supplement group compared with the non-vitamin D supplement groupSignificant improvement of the median UAS7 score in the vitamin D supplement group than in the non-vitamin D supplement groupSignificantly improvement of the median DLQI score in the vitamin D supplement compared with the non-vitamin D supplement groupNone of the patients in the vitamin D supplement group were symptom-free at the optimal vitamin D levels. | |||||||||||

| Ariaee et al. [19] | Prospective study | 20 | CSUSerum vitamin D concentration<10ng/mL | ND | Vitamin D 50,000 unit/week | 8weeks | USSDLQI | ND | ND | USS (meanSD) | DLQI scores (meanSD) |

| Before | After | Before | After | ||||||||

| 23513.9 | 11.29.6 | 10.81.6 | 0.94.8 | ||||||||

| Significant reduction in USS after vitamin D supplementImprovement of DLQI (55%) after vitamin D supplementIncrease FOXP3 gene expression and downregulation of IL-10, TGF-beta and FOXP3, IL-17 after vitamin D supplement | |||||||||||

| Dabas et al. [32] | Randomized controlled trial | 200 | CSUSerum 25(OH)D<30nmol/L | Levocetirizine 10mg/day | Group AVitamin D 2000IU/dayGroup BVitamin D 60,000IU/weekGroup CNone | 12weeks | UAS4 | ND | ND | UAS4 (mean) | |

| Before | After 6weeks | After 12weeks | |||||||||

| Group A | |||||||||||

| 11.87.6 | 6.66.0 | 5.35.2 | |||||||||

| Group B | |||||||||||

| 13.08.0 | 6.45.0 | 4.23.5 | |||||||||

| Group C | |||||||||||

| 12.97.03 | 8.05.7 | 6.14.8 | |||||||||

| No significant difference in mean UAS4 in the 3 groups after 12weeks of vitamin D replacementVitamin D replacement decreased the severity in most patients. |

The parameters of treatment outcomes varied among the studies; they comprised the urticaria activity score over 4days (UAS4) [24, 32], urticaria activity score over 7days (UAS7) [31], dermatology life quality index [19, 31], chronic urticaria quality of life questionnaire [24], visual analogue scale [25], 5-dimension itch score [25], and urticaria symptom severity score [19, 26] (Table). Four studies reported a significant reduction in disease activity after high dose vitamin D supplementation (vitamin D2, 140,000IU/week; vitamin D3, 60,00075,000IU/week; and unknown form of vitamin D, 50,000 unit/week) [19, 24, 25, 31]. One case report showed that treatment with a low vitamin D dosage (400IU/d) for 2months did not reduce urticaria activity. However, complete resolution without antihistamine was demonstrated at a higher dosage (2000IU/d) [27]. Another study reported a significant reduction in disease activity after high-dose vitamin D supplementation (4000IU/d) compared to low-dose vitamin D supplementation (600IU/d) [26]. Ariaee et al. reported that the transforming growth factor-, IL-10 and IL-17 expressions were decreased after 8weeks of vitamin D supplementation [19]. In addition, forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) expression, a clinical determinant of Treg, increased after treatment [19]. In the RCT study, either low-dose or high-dose of vitamin D supplementation could reduce disease severity but there was no significant difference in the mean UAS4 among the three groups after 12weeks of supplementation [32].

Table5

Summarized of treatment regimens and outcome of vitamin D supplementation

| N | Sindher et al. [27]** | Rorie et al. [26] | Rasool et al. [25] | Oguz Topal et al. [24] | Boonpiyathad et al. [31] | Ariaee et al. [19] | Dabas et al. [32] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | 21 | 48 | 57 | 57 | 50 | 20 | 200 | ||||||

| Intervention | Vitamin D3400IU/day | Vitamin D32000IU/day | Vitamin D34000IU/day | Vitamin D3600IU/day | Vitamin D360,000IU/week | Vitamin D3 60,000IU/week,4weeksHydroxyzine25mg/day, 6weeksCorticosteroid6mg/day, 6weeks | Vitamin D3300,000IU/month | Vitamin D220,000IU/day | Vitamin D(unknown form)50,000 unit/week | Vitamin D (unknown form)Group AVitamin D 2000IU/dayGroup BVitamin D 60,000IU/weekGroup CNone | ||||

| Duration | 8weeks | ND | 12weeks | 12weeks | 4weeks | 4weeks | 12weeks | 6weeks | 8weeks | 12weeks | ||||

| Vitamin D status (ng/mL) | ||||||||||||||

| Before treatment | 4.7 | ND | 28.82.2 | 37.13.4 | 16.981.43 | 18.951.42 | ND | 13 (829)median (minmax) | ND | ND | ||||

| End of treatment | ND | 65 | 56.03.9 | 35.82.3 | 56.743.76(p<0 .0001) | 41.732.85(p<0.0001) | ND | 40 (2862)median (minmax) | ND | ND | ||||

| Outcome | Continued to have intermittent urticaria | Complete resolution without antihistamine | Decrease total USS scores(meanSE) | VAS score(meanSEM) | UAS4(median(minmax)) | UAS7 | USS(meanSD) | UAS4 (mean) | ||||||

| 15.02.9(p=0.02) | 24.14.0 | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After 6weeks | After 12weeks |

| 6.70.04 | 5.20.70p=0.009 | 6.680.40 | 1.860.39p<0.0001 | 21(042.0) | 6(021.0)p<0.001 | 27(638) | 15(233) | 23513.9 | 11.29.6 | GroupA | ||||

| 11.87.6 | 6.66.0 | 5.35.2 | ||||||||||||

| 5-D itch score(mean) | CU-Q2oL(median(minmax)) | DLQI scores | DLQI scores(meanSD) | Group B | ||||||||||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | 13.08.0 | 6.45.0 | 4.23.5 | ||

| 14.50.72 | 12.061.10p=0.007 | 13.90.68 | 5.010.94p<0.0001 | 38 (6.5115.2) | 10.8(043.4)p<0.001 | 13(431) | 6(120) | 10.81.6 | 0.94.8 | Group C | ||||

| 12.97.03 | 8.05.7 | 6.14.8 |

Discussion

Two recent meta-analysis regarding the association between vitamin D and urticaria have been published in 2018. Tsai et al. and Wang et al. showed that the prevalence of vitamin D was significantly higher in CU patients than that of controls. [34, 35] Similar to those two meta-analysis, 12 out of 14 studies in our study showed significantly lower levels of serum vitamin D in CSU patients than in the controls [14, 18, 20, 21, 2325, 28, 29, 31, 33]. Only Wu et al. found significantly higher levels of vitamin D in the CSU patients than in the UK general population as a control group [30]. However, that study compared CSU patients in Southampton General Hospital to the UK general population rather than healthy controls in Southampton; a variation of serum vitamin D levels in different regions of UK was reported [36]. Lee et al. [22] reported no statistical significance between the vitamin D levels in pediatric CSU patients and the controls, which was similar to a study by Tsai et al. [34]. Nevertheless, it should be noted that our study provides additional information regarding associations between vitamin D and urticaria than those of the two studies. Data regarding (1) types of serum vitamin D (2) outcome of vitamin D supplementation after treating with different dosages, types and duration of vitamin D are also added in this study.

Potential factors determining vitamin D status include oral vitamin D intake, sun exposure, latitude, season, Fitzpatrick skin type, time spent outdoors, sun exposure practices, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, alcohol intake, and genetic polymorphism [37]. Higher serum vitamin D levels can be observed with prolonged sun exposure, increased time spent outdoors, the summer season, living in lower latitudes, increased physical activity, moderate alcohol intake, and rs7041 gene polymorphism [37]. In contrast, lower serum vitamin D levels can be observed with darker skin, female gender, higher BMI, excessive alcohol intake, and rs4588 gene polymorphism [37]. It has been reported that vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is a pandemic problem. The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency has been estimated to be 30%-60% of children and adults worldwide. Areas that had high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in the general population were Europe (92%), Middle East (90%), Asia (4598%), and Canada (61%). The most common cause of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is an insufficient exposure to sun-light as diet with fortified vitamin D are few. For example, in Middle East, vitamin D deficiency is found to strongly correlate with well-covering clothes [38, 39].

Vitamin D has been shown to be linked to other skin diseases. Low serum 25(OH)D levels have been reported in severe atopic dermatitis [40], psoriasis [41], vitiligo [42], systemic sclerosis [43], severe alopecia areata [44], severe systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [45], and acne [46] and also associated with an increased risk of cutaneous bacterial infections in vitro [47]. However, no studies in our review reported the cut-off serum vitamin D levels that might be associated with the development of CSU.

As to vitamin D supplementation, both vitamins D2 and D3 are commonly. Current dietary reference intakes for vitamin D are 400IU per day in infancy, 600IU per day in the 170year age group, and 800IU per day for individuals aged over 70 [48]. Vitamin D2 is reported to be less effective than vitamin D3 in raising total serum vitamin D levels, but less toxic than vitamin D3 when given in large amounts [2]. The variations in the vitamin D supplementation regimens in the studies might have led to different outcomes.

Six studies showed that a high dosage of vitamin D treatment resulted in a significant reduction in CSU activity. [19, 2427, 31] The other study reported that vitamin D supplement 2000IU/day and 60,000IU/week decreased disease activity in most CSU patients [32].

Among the various regimens, higher dosages of vitamin D (vitamin D3 of at least 28,000IU/week for 412weeks, or vitamin D2 of 140,000IU/week for 6weeks) were reported to be effective. Although the available studies were relatively scarce, CSU patients with low serum vitamin D levels at baseline tended to show an improvement after receiving high dose vitamin D supplementation. Vitamin D has high safety margin. The tolerable upper intake levels are now 400010,000IU/d for adults and the elderly, and lower for infants and young children [48, 49]. According to our systematic review, even though there were not reported any adverse effect during vitamin D therapy, high dosage of vitamin D use should be concerned about safety. Measurement of serum vitamin D levels may be useful for safety monitoring and determining relationship to the treatment outcome, and it should be concerned about potential adverse effect at serum 25(OH)D levels greater than 50ng/ml (125nmol/liter) [48].

Vitamin D supplementation was reported for other skin diseases. A meta-analysis by Kim et al. of 4 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials showed that the SCORAD index and EASI score of atopic dermatitis patients decreased significantly after vitamin D supplementation [50]. Lim et al. compared the vitamin D levels of patients with and without acne in a casecontrol study combined with a randomized controlled trial [46]. Improvements in inflammatory lesions were noted after vitamin D supplementation in 39 acne patients with 25(OH)D deficiency. AbouRaya et al. randomized 267 patients with SLE to receive either vitamin D3 (2000IU daily) or a placebo. At 12months of treatment, there was a significant decrease in the pro-inflammatory cytokines levels (i.e., IL-1, IL-6, IL-18 and TNF-), anti-dsDNA, C4, fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, and disease activity scores of the treatment group compared to the placebo group [51].

This systematic review has some limitations. First, there are small numbers of relevant studies. Second, few studies are RCTs; and variety in the individualized vitamin D supplementation regimens contribute to unsettle treatment results.

Conclusions

Most studies showed that CSU patients had significantly lower serum vitamin D levels than the controls [14, 18, 20, 21, 2325, 28, 29, 3133]. However, this relationship does not prove causation. Data from a limited number of studies showed that the responders tended to be CSU patients with low serum vitamin D at baseline who received high-dose vitamin D supplementation regimens. For recalcitrant CSU patients with low serum vitamin D levels, a high dose of vitamin D supplements for 412weeks may be used as an adjunctive treatment. Well-designed randomized placebo-controlled studies should be performed to determine the cut-off levels for vitamin D supplementation and treatment outcomes.

Authors contributions

SA performed literature search of electronic databases. KK and SA screened articles for eligibility based on the inclusion criterion and assessed the risk of bias. PT and SA reviewed and extracted information from the eligible full-text articles. KK, PT, and LC contributed to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Saowalak Hunnangkul, Ph.D. Biostatistician, for assistance with the statistical analyses.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by Siriraj Institutional Review Board, protocol No. 586/2560(Exempt).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Publishers Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

| 1,25(OH)2D | 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D |

| 25(OH)D | 25-hydroxyvitamin D |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CIU | chronic idiopathic urticaria |

| CSU | chronic spontaneous urticaria |

| CU | chronic urticaria |

| GC | group-specific component |

| IL | interleukin |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| SLE | systemic lupus erythematosus |

| SNPs | single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| Treg cells | regulatory T cells |

| UAS | urticaria activity score |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| VDBP | vitamin D binding protein |

| VDR | vitamin D receptor |

Contributor Information

Papapit Tuchinda, Email: moc.liamg@ttipapap.

Kanokvalai Kulthanan, Phone: +66 (0) 2419 4333, Email: [email protected].

Leena Chularojanamontri, Email: moc.liamg@mijaneel.

Sittiroj Arunkajohnsak, Email: moc.liamtoh@jorittis_pot.

Sutin Sriussadaporn, Email: ht.ca.lodiham@irs_nitus.

References

1.

Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Brzoza Z, Canonica GW, et al. The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014;69:868887. doi:10.1111/all.12313. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]2.

Rosen CJ. Clinical practice. Vitamin D insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:248254. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1009570. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]3.

Ko JA, Lee BH, Lee JS, Park HJ. Effect of UV-B exposure on the concentration of vitamin D2 in sliced shiitake mushroom (Lentinus edodes) and white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:36713674. doi:10.1021/jf073398s. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]4.

Deluca HF, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D: its role and uses in immunology. FASEB J. 2001;15:25792585. doi:10.1096/fj.01-0433rev. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]5.

Yu C, Fedoric B, Anderson PH, Lopez AF, Grimbaldeston MA. Vitamin D(3) signalling to mast cells: a new regulatory axis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:4146. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2010.10.011. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]6.

Hata TR, Kotol P, Boguniewicz M, Taylor P, Paik A, Jackson M, et al. History of eczema herpeticum is associated with the inability to induce human beta-defensin (HBD)-2, HBD-3 and cathelicidin in the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:659661. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09892.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]7.

Kongsbak M, von Essen MR, Levring TB, Schjerling P, Woetmann A, Odum N, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein controls T cell responses to vitamin D. BMC Immunol. 2014;15:35. doi:10.1186/s12865-014-0035-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]8.

Cheng HM, Kim S, Park GH, Chang SE, Bang S, Won CH, et al. Low vitamin D levels are associated with atopic dermatitis, but not allergic rhinitis, asthma, or IgE sensitization, in the adult Korean population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:10481055. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.055. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]9.

Di Filippo P, Scaparrotta A, Rapino D, Cingolani A, Attanasi M, Petrosino MI, et al. Vitamin D supplementation modulates the immune system and improves atopic dermatitis in children. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2015;166:9196. doi:10.1159/000371350. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]10.

Baroni E, Biffi M, Benigni F, Monno A, Carlucci D, Carmeliet G, et al. VDR-dependent regulation of mast cell maturation mediated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:250262. doi:10.1189/jlb.0506322. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]11.

Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, Zonderman AB, Berg AH, Nalls M, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:19912000. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1306357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]12.

Zhang J, Chalmers MJ, Stayrook KR, Burris LL, Wang Y, Busby SA, et al. DNA binding alters coactivator interaction surfaces of the intact VDR-RXR complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:556563. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2046. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]13.

Bizzaro G, Antico A, Fortunato A, Bizzaro N. Vitamin D and autoimmune diseases: is vitamin D receptor (VDR) polymorphism the culprit? Isr Med Assoc J. 2017;19:438443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]14.

Nasiri-Kalmarzi R, Abdi M, Hosseini J, Babaei E, Mokarizadeh A, Vahabzadeh Z. Evaluation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 pathway in patients with chronic urticaria. QJM. 2018;111(3):161169. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx223. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]15.

Abuzeid WM, Akbar NA, Zacharek MA. Vitamin D and chronic rhinitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:1317. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834eccdb. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]16.

Osborne NJ, Ukoumunne OC, Wake M, Allen KJ. Prevalence of eczema and food allergy is associated with latitude in Australia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:865867. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.037. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]18.

Abdel-Rehim AS, Sheha DS, Mohamed NA. Vitamin D level among Egyptian patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria and its relation to severity of the disease. Egypt J Immunol. 2014;21:8590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]19.

Ariaee N, Zarei S, Mohamadi M, Jabbari F. Amelioration of patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria in treatment with vitamin D supplement. Clin Mol Allergy. 2017;15:22. doi:10.1186/s12948-017-0078-z. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]20.

Chandrashekar L, Rajappa M, Munisamy M, Ananthanarayanan PH, Thappa DM, Arumugam B. 25-Hydroxy vitamin D levels in chronic urticaria and its correlation with disease severity from a tertiary care centre in South India. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52:115118. doi:10.1515/cclm-2013-1014. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]21.

Grzanka A, Machura E, Mazur B, Misiolek M, Jochem J, Kasperski J, et al. Relationship between vitamin D status and the inflammatory state in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Inflamm (Lond) 2014;11:2. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-11-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]22.

Lee SJ, Ha EK, Jee HM, Lee KS, Lee SW, Kim MA, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of urticaria with a focus on chronic urticaria in children. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:212219. doi:10.4168/aair.2017.9.3.212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]23.

Movahedi M, Tavakol M, Hirbod-Mobarakeh A, Gharagozlou M, Aghamohammadi A, Tavakol Z, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;14:222227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]24.

Oguz Topal I, Kocaturk E, Gungor S, Durmuscan M, Sucu V, Yildirmak S. Does replacement of vitamin D reduce the symptom scores and improve quality of life in patients with chronic urticaria? J Dermatol Treat. 2016;27:163166. doi:10.3109/09546634.2015.1079297. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]25.

Rasool R, Masoodi KZ, Shera IA, Yosuf Q, Bhat IA, Qasim I, et al. Chronic urticaria merits serum vitamin D evaluation and supplementation; a randomized case control study. World Allergy Organ J. 2015;8:15. doi:10.1186/s40413-015-0066-z. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]26.

Rorie A, Goldner WS, Lyden E, Poole JA. Beneficial role for supplemental vitamin D3 treatment in chronic urticaria: a randomized study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(4):376382. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2014.01.010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]27.

Sindher SB, Jariwala S, Gilbert J, Rosenstreich D. Resolution of chronic urticaria coincident with vitamin D supplementation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:359360. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2012.07.025. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]28.

Thorp WA, Goldner W, Meza J, Poole JA. Reduced vitamin D levels in adult subjects with chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:413. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.040. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]29.

Woo YR, Jung KE, Koo DW, Lee JS. Vitamin D as a marker for disease severity in chronic urticaria and its possible role in pathogenesis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:423430. doi:10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.423. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]30.

Wu CH, Eren E, Ardern-Jones MR, Venter C. Association between micronutrient levels and chronic spontaneous urticaria. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:926167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]31.

Boonpiyathad T, Pradubpongsa P, Sangasapaviriya A. Vitamin D supplements improve urticaria symptoms and quality of life in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients: a prospective case-control study. Dermato-Endocrinology. 2016;8:983685. doi:10.4161/derm.29727. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] Retracted32.

Dabas G, Kumaran MS, Prasad D. Vitamin D in chronic urticaria: unrevealing the enigma. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:4748. doi:10.1111/bjd.15015. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]33.

Rather S, Keen A, Sajad P. Serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in chronic urticaria and its association with disease activity: a case control study. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:170174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]34.

Tsai TY, Huang YC. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with chronic and acute urticaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:573575. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.033. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]35.

Wang X, Li X, Shen Y, Wang X. The association between serum vitamin D levels and urticaria: a meta-analysis of observational studies. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:389395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]36.

Hypponen E, Power C. Hypovitaminosis D in British adults at age 45 y: nationwide cohort study of dietary and lifestyle predictors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:860868. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.3.860. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]37.

Kechichian E, Ezzedine K. Vitamin D and the skin: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:223235. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0323-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]38.

Holick MF. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18:153165. doi:10.1007/s11154-017-9424-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]39.

van Schoor NM, Lips P. Worldwide vitamin D status. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25:671680. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2011.06.007. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]40.

Heine G, Hoefer N, Franke A, Nothling U, Schumann RR, Hamann L, et al. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:855858. doi:10.1111/bjd.12077. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]41.

Bergler-Czop B, Brzezinska-Wcislo L. Serum vitamin D levelthe effect on the clinical course of psoriasis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:445449. doi:10.5114/ada.2016.63883. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]42.

Upala S, Sanguankeo A. Low 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are associated with vitiligo: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2016;32:181190. doi:10.1111/phpp.12241. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]43.

Giuggioli D, Colaci M, Cassone G, Fallahi P, Lumetti F, Spinella A, et al. Serum 25-OH vitamin D levels in systemic sclerosis: analysis of 140 patients and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:583590. doi:10.1007/s10067-016-3535-z. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]44.

Aksu Cerman A, Sarikaya Solak S, Kivanc Altunay I. Vitamin D deficiency in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:12991304. doi:10.1111/bjd.12980. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]45.

Wu PW, Rhew EY, Dyer AR, Dunlop DD, Langman CB, Price H, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and cardiovascular risk factors in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:13871395. doi:10.1002/art.24785. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]46.

Lim SK, Ha JM, Lee YH, Lee Y, Seo YJ, Kim CD, et al. Comparison of vitamin D levels in patients with and without acne: a case-control study combined with a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:0161162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]47.

Muehleisen B, Bikle DD, Aguilera C, Burton DW, Sen GL, Deftos LJ, et al. PTH/PTHrP and vitamin D control antimicrobial peptide expression and susceptibility to bacterial skin infection. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:135ra66-ra66. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]48.

Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:5358. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-2704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]49.

Pludowski P, Holick MF, Grant WB, Konstantynowicz J, Mascarenhas MR, Haq A, et al. Vitamin D supplementation guidelines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;175:125135. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.01.021. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]50.

Kim MJ, Kim SN, Lee YW, Choe YB, Ahn KJ. Vitamin D status and efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2016;8:789. doi:10.3390/nu8120789. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]51.

Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S, Helmii M. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on inflammatory and hemostatic markers and disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:265272. doi:10.3899/jrheum.111594. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]