What are the first signs of rabies in humans

Signs and symptoms of rabies

Rabies infection and prognosis

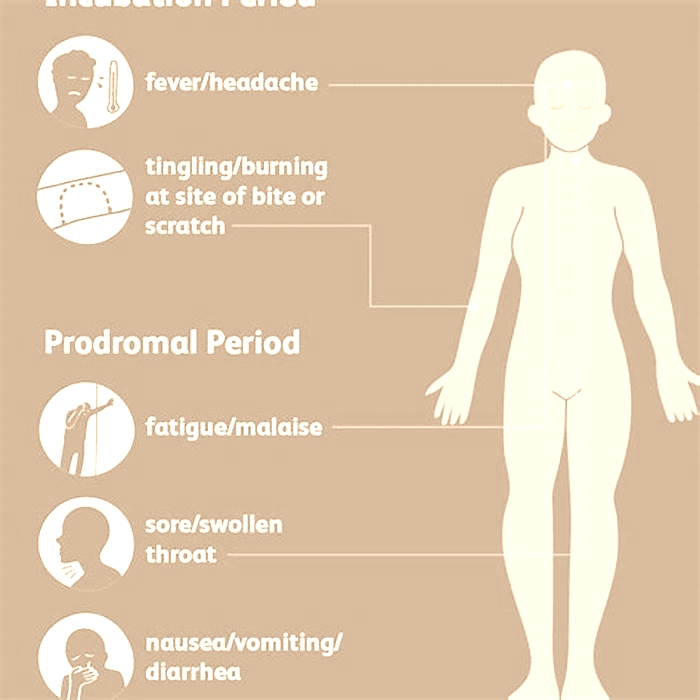

Following exposure to the virus, the onset of symptoms can take anywhere from a few days to over a year to occur, with the average time being 1 to 12 weeks in people. The time taken depends on how long it takes the virus to travel from the wound site to the brain, which is when symptoms begin. This is based on several factors, including where the infection occurred (distance from brain), how much of the virus entered the body, and the size of the infected individual (or animal). Therefore, if a large man was bitten on the foot, the time to onset of symptoms may be longer than if a small child was bitten on the face.

Rabies Symptoms

Rabies symptoms in people

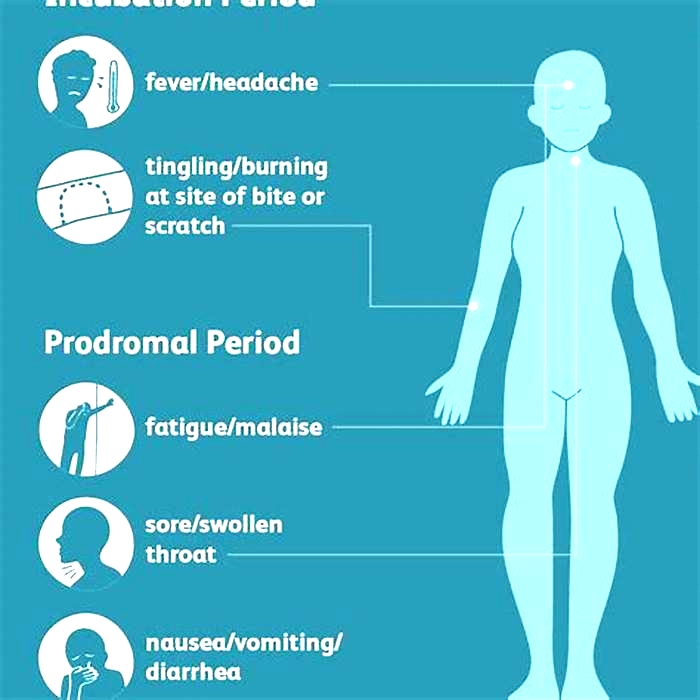

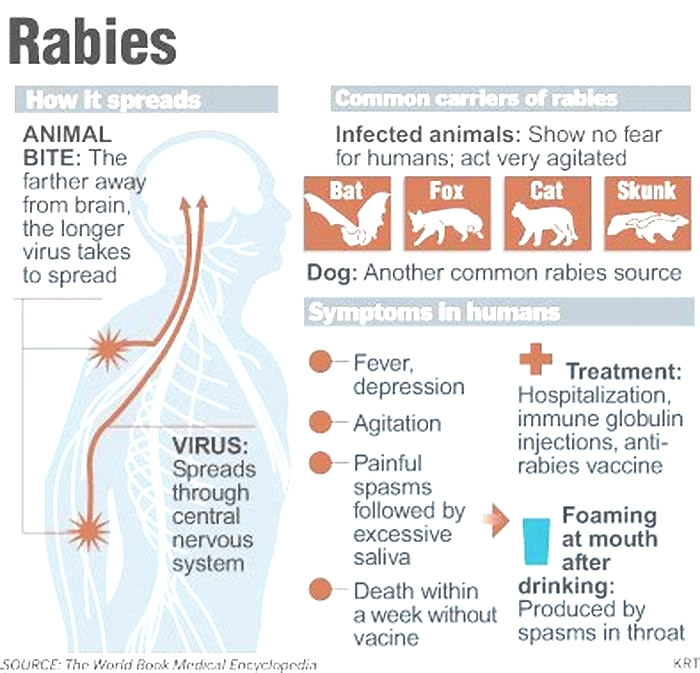

The initial symptoms of rabies are similar to those of the flu - fever, headache, and generally feeling unwell. As the disease progresses, the person can experience delirium, abnormal behaviour, and hallucinations, as well as the infamous hydrophobia and foaming at the mouth (related to the paralysis of swallowing muscles). It is important to note however, that rabies symptoms can vary greatly, meaning that not every person will demonstrate all (or even many) of the typical symptoms.

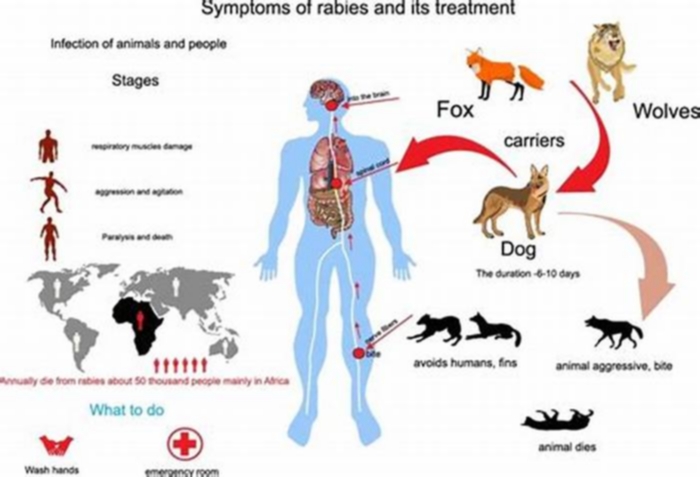

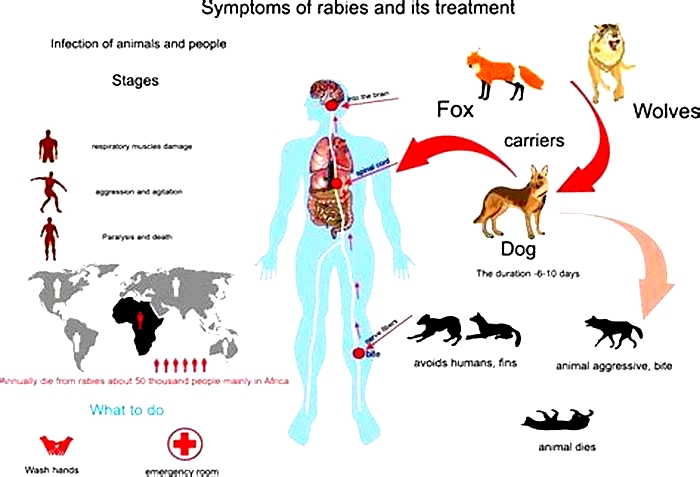

Signs of rabies in animals

Rabies signs in animals are similar, with a change in behavior (either an aggressive or wild animal becoming tame and calm, or a calm animal becoming aggressive), paralysis or partial paralysis in many cases, abnormal vocalization (dogs barking strangely), animals attacking inanimate objects (like biting rocks or trees), hydrophobia and foaming at the mouth, among others. However, rabies in animals is even more difficult to diagnose without laboratory testing as the signs can vary so much in different cases. One thing is sure, is that all cases of rabies will eventually result in death once signs are present.

Why do we interchange the use of symptoms versus signs?

Symptoms refer to the disease in humans. People are able to more accurately describe their symptoms (how they feel, what the disease looks like, what is happening with the disease) to medical professionals, whereas veterinarians need to rely on the signs that are detectable in the animal, as the animal is not able to accurately describe how it feels and what may be occurring when the disease manifests.

Rabies

Jason Howland:The most dangerous threat of rabies in the U.S. is flying overhead.

Gregory Poland, M.D., Vaccine Research Group Mayo Clinic:"It used to be thought, well, it's a rabid dog. But the more common way of getting rabies is from the silver-haired bat."

Jason Howland:The deadly virus is transmitted from the saliva of infected animals to humans, usually through a bite.

Dr. Poland:" The bat doesn't always bite. Sometimes the saliva will drool onto you, and you could have a minor open cut. Or sometimes a bat will lick on the skin and, again, transmit the virus that way."

Jason Howland:Dr. Poland says that's why if you wake up and find a bat in the room, you should get the rabies vaccine.

Dr. Poland:"People think, 'Well, the bat's in the house. We woke up with it, doesn't look like it bit anybody.' Doesn't matter. Rabies is such a severe disease with no cure, no treatment for it, that the safer thing to do is to give rabies vaccine."

Jason Howland:That includes an immune globulin and multidose rabies series which is not cheap. A typical series of rabies vaccines cost anywhere from three to seven thousand dollars.

For the Mayo Clinic News Network, I'm Jason Howland.

Rabies

Deadly viral disease, transmitted through animals

Medical condition

| Rabies | |

|---|---|

| |

| A man with rabies, 1958 | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, extreme aversion to water, confusion, excessive salivary secretion, hallucinations, disrupted sleep, paralysis, coma,[1][2] hyperactivity, headache, nausea, vomiting, anxiety[3] |

| Causes | Rabies virus, Australian bat lyssavirus[4] |

| Prevention | Rabies vaccine, animal control, rabies immunoglobulin[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care |

| Medication | Incurable[5] |

| Prognosis | ~100% fatal after onset of symptoms[1] |

| Deaths | 59,000 per year worldwide[6] |

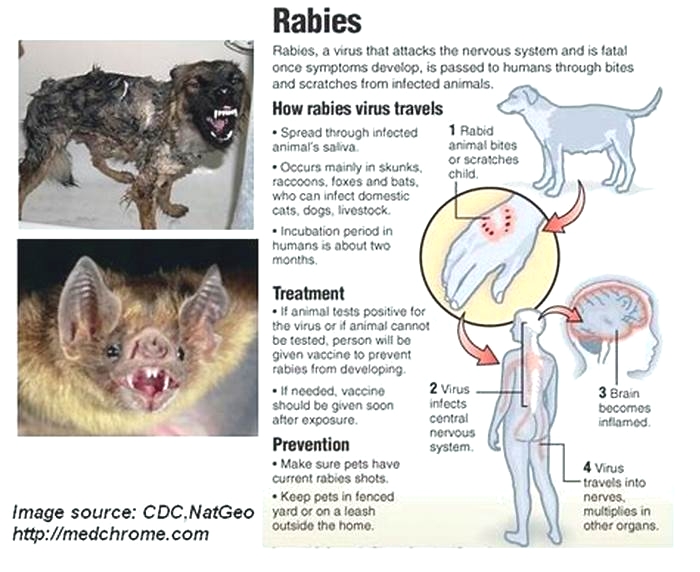

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals.[1] It was historically referred to as hydrophobia ("fear of water") due to the symptom of panic when presented with liquids to drink. Early symptoms can include fever and abnormal sensations at the site of exposure.[1] These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, violent movements, uncontrolled excitement, fear of water, an inability to move parts of the body, confusion, and loss of consciousness.[1][7][8][9] Once symptoms appear, the result is virtually always death.[1] The time period between contracting the disease and the start of symptoms is usually one to three months but can vary from less than one week to more than one year.[1] The time depends on the distance the virus must travel along peripheral nerves to reach the central nervous system.[10]

Rabies is caused by lyssaviruses, including the rabies virus and Australian bat lyssavirus.[4] It is spread when an infected animal bites or scratches a human or other animals.[1] Saliva from an infected animal can also transmit rabies if the saliva comes into contact with the eyes, mouth, or nose.[1] Globally, dogs are the most common animal involved.[1] In countries where dogs commonly have the disease, more than 99% of rabies cases are the direct result of dog bites.[11] In the Americas, bat bites are the most common source of rabies infections in humans, and less than 5% of cases are from dogs.[1][11] Rodents are very rarely infected with rabies.[11] The disease can be diagnosed only after the start of symptoms.[1]

Animal control and vaccination programs have decreased the risk of rabies from dogs in a number of regions of the world.[1] Immunizing people before they are exposed is recommended for those at high risk, including those who work with bats or who spend prolonged periods in areas of the world where rabies is common.[1] In people who have been exposed to rabies, the rabies vaccine and sometimes rabies immunoglobulin are effective in preventing the disease if the person receives the treatment before the start of rabies symptoms.[1] Washing bites and scratches for 15 minutes with soap and water, povidone-iodine, or detergent may reduce the number of viral particles and may be somewhat effective at preventing transmission.[1][12] As of 2016[update], only fourteen people were documented to have survived a rabies infection after showing symptoms.[13][14] However, research conducted in 2010 among a population of people in Peru with a self-reported history of one or more bites from vampire bats (commonly infected with rabies), found that out of 73 individuals reporting previous bat bites, seven people had rabies virus-neutralizing antibodies (rVNA).[15] Since only one member of this group reported prior vaccination for rabies, the findings of the research suggest previously undocumented cases of infection and viral replication followed by an abortive infection. This could indicate that people may have an exposure to the virus without treatment and develop natural antibodies as a result.

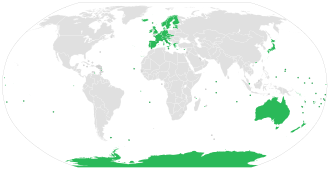

Rabies causes about 59,000 deaths worldwide per year,[6] about 40% of which are in children under the age of 15.[16] More than 95% of human deaths from rabies occur in Africa and Asia.[1] Rabies is present in more than 150 countries and on all continents but Antarctica.[1] More than 3billion people live in regions of the world where rabies occurs.[1] A number of countries, including Australia and Japan, as well as much of Western Europe, do not have rabies among dogs.[17][18] Many Pacific islands do not have rabies at all.[18] It is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[19]

Etymology

The name rabies is derived from the Latin rabies, "madness".[20] The Greeks derived the word lyssa, from lud or "violent"; this root is used in the genus name of the rabies virus, Lyssavirus.[21]

Signs and symptoms

The period between infection and the first symptoms (incubation period) is typically one to three months in humans.[22] This period may be as short as four days or longer than six years, depending on the location and severity of the wound and the amount of virus introduced.[22] Initial symptoms of rabies are often nonspecific such as fever and headache.[22] As rabies progresses and causes inflammation of the brain and meninges, symptoms can include slight or partial paralysis, anxiety, insomnia, confusion, agitation, abnormal behavior, paranoia, terror, and hallucinations.[10][22] The person may also have fear of water.[1]

The symptoms eventually progress to delirium, and coma.[10][22] Death usually occurs two to ten days after first symptoms. Survival is almost unknown once symptoms have presented, even with intensive care.[22][23]

Rabies has also occasionally been referred to as hydrophobia ("fear of water") throughout its history.[24] It refers to a set of symptoms in the later stages of an infection in which the person has difficulty swallowing, shows panic when presented with liquids to drink, and cannot quench their thirst. Saliva production is greatly increased, and attempts to drink, or even the intention or suggestion of drinking, may cause excruciatingly painful spasms of the muscles in the throat and larynx. Since the infected individual cannot swallow saliva and water, the virus has a much higher chance of being transmitted, because it multiplies and accumulates in the salivary glands and is transmitted through biting.[25]

Hydrophobia is commonly associated with furious rabies, which affects 80% of rabies-infected people. This form of rabies causes irrational aggression in the host, which aids in the spreading of the virus through animal bites;[26][medical citation needed] a "foaming at the mouth" effect, caused by the accumulation of saliva, is also commonly associated with rabies in the public perception and in popular culture.[27][28][29] The remaining 20% may experience a paralytic form of rabies that is marked by muscle weakness, loss of sensation, and paralysis; this form of rabies does not usually cause fear of water.[30]

Cause

Rabies is caused by a number of lyssaviruses including the rabies virus and Australian bat lyssavirus.[4] Duvenhage lyssavirus may cause a rabies-like infection.[31]

The rabies virus is the type species of the Lyssavirus genus, in the family Rhabdoviridae, order Mononegavirales. Lyssavirions have helical symmetry, with a length of about 180nm and a cross-section of about 75nm.[32] These virions are enveloped and have a single-stranded RNA genome with negative sense. The genetic information is packed as a ribonucleoprotein complex in which RNA is tightly bound by the viral nucleoprotein. The RNA genome of the virus encodes five genes whose order is highly conserved: nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), glycoprotein (G), and the viral RNA polymerase (L).[33]

To enter cells, trimeric spikes on the exterior of the membrane of the virus interact with a specific cell receptor, the most likely one being the acetylcholine receptor. The cellular membrane pinches in a procession known as pinocytosis and allows entry of the virus into the cell by way of an endosome. The virus then uses the acidic environment, which is necessary, of that endosome and binds to its membrane simultaneously, releasing its five proteins and single-strand RNA into the cytoplasm.[34]

Once within a muscle or nerve cell, the virus undergoes replication. The L protein then transcribes five mRNA strands and a positive strand of RNA all from the original negative strand RNA using free nucleotides in the cytoplasm. These five mRNA strands are then translated into their corresponding proteins (P, L, N, G and M proteins) at free ribosomes in the cytoplasm. Some proteins require post-translational modifications. For example, the G protein travels through the rough endoplasmic reticulum, where it undergoes further folding, and is then transported to the Golgi apparatus, where a sugar group is added to it (glycosylation).[34]

When there are enough viral proteins, the viral polymerase will begin to synthesize new negative strands of RNA from the template of the positive-strand RNA. These negative strands will then form complexes with the N, P, L and M proteins and then travel to the inner membrane of the cell, where a G protein has embedded itself in the membrane. The G protein then coils around the N-P-L-M complex of proteins taking some of the host cell membrane with it, which will form the new outer envelope of the virus particle. The virus then buds from the cell.[34]

From the point of entry, the virus is neurotropic, traveling along the neural pathways into the central nervous system. The virus usually first infects muscle cells close to the site of infection, where they are able to replicate without being 'noticed' by the host's immune system. Once enough virus has been replicated, they begin to bind to acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction.[35] The virus then travels through the nerve cell axon via retrograde transport, as its P protein interacts with dynein, a protein present in the cytoplasm of nerve cells. Once the virus reaches the cell body it travels rapidly to the central nervous system (CNS), replicating in motor neurons and eventually reaching the brain.[10] After the brain is infected, the virus travels centrifugally to the peripheral and autonomic nervous systems, eventually migrating to the salivary glands, where it is ready to be transmitted to the next host.[36]:317

Transmission

All warm-blooded species, including humans, may become infected with the rabies virus and develop symptoms. Birds were first artificially infected with rabies in 1884; however, infected birds are largely, if not wholly, asymptomatic, and recover.[37] Other bird species have been known to develop rabies antibodies, a sign of infection, after feeding on rabies-infected mammals.[38][39]

The virus has also adapted to grow in cells of cold-blooded vertebrates.[40][41] Most animals can be infected by the virus and can transmit the disease to humans. Worldwide, about 99% of human rabies cases come from domestic dogs.[42] Other sources of rabies in humans include bats,[43][44] monkeys, raccoons, foxes, skunks, cattle, wolves, coyotes, cats, and mongooses (normally either the small Asian mongoose or the yellow mongoose).[45]

Rabies may also spread through exposure to infected bears, domestic farm animals, groundhogs, weasels, and other wild carnivorans. However, lagomorphs, such as hares and rabbits, and small rodents, such as chipmunks, gerbils, guinea pigs, hamsters, mice, rats, and squirrels, are almost never found to be infected with rabies and are not known to transmit rabies to humans.[46] Bites from mice, rats, or squirrels rarely require rabies prevention because these rodents are typically killed by any encounter with a larger, rabid animal, and would, therefore, not be carriers.[47] The Virginia opossum (a marsupial, unlike the other mammals named in this paragraph, which are all eutherians/placental), has a lower internal body temperature than the rabies virus prefers and therefore is resistant but not immune to rabies.[48] Marsupials, along with monotremes (platypuses and echidnas), typically have lower body temperatures than similarly sized eutherians.[49]

The virus is usually present in the nerves and saliva of a symptomatic rabid animal.[50][51] The route of infection is usually, but not always, by a bite. In many cases, the infected animal is exceptionally aggressive, may attack without provocation, and exhibits otherwise uncharacteristic behavior.[52] This is an example of a viral pathogen modifying the behavior of its host to facilitate its transmission to other hosts. After a typical human infection by bite, the virus enters the peripheral nervous system. It then travels retrograde along the efferent nerves toward the central nervous system.[53] During this phase, the virus cannot be easily detected within the host, and vaccination may still confer cell-mediated immunity to prevent symptomatic rabies. When the virus reaches the brain, it rapidly causes encephalitis, the prodromal phase, which is the beginning of the symptoms. Once the patient becomes symptomatic, treatment is almost never effective and mortality is over 99%. Rabies may also inflame the spinal cord, producing transverse myelitis.[54][55]

Although it is theoretically possible for rabies-infected humans to transmit it to others by biting or otherwise, no such cases have ever been documented, because infected humans are usually hospitalized and necessary precautions taken. Casual contact, such as touching a person with rabies or contact with non-infectious fluid or tissue (urine, blood, feces), does not constitute an exposure and does not require post-exposure prophylaxis. But as the virus is present in sperm and vaginal secretions, it might be possible for rabies to spread through sex.[56] There are only a small number of recorded cases of human-to-human transmission of rabies, and all occurred through organ transplants, most frequently with corneal transplantation, from infected donors.[57][58]

Diagnosis

Rabies can be difficult to diagnose because, in the early stages, it is easily confused with other diseases or even with a simple aggressive temperament.[59] The reference method for diagnosing rabies is the fluorescent antibody test (FAT), an immunohistochemistry procedure, which is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).[60] The FAT relies on the ability of a detector molecule (usually fluorescein isothiocyanate) coupled with a rabies-specific antibody, forming a conjugate, to bind to and allow the visualisation of rabies antigen using fluorescent microscopy techniques. Microscopic analysis of samples is the only direct method that allows for the identification of rabies virus-specific antigen in a short time and at a reduced cost, irrespective of geographical origin and status of the host. It has to be regarded as the first step in diagnostic procedures for all laboratories. Autolysed samples can, however, reduce the sensitivity and specificity of the FAT.[61] The RT PCR assays proved to be a sensitive and specific tool for routine diagnostic purposes,[62] particularly in decomposed samples[63] or archival specimens.[64] The diagnosis can be reliably made from brain samples taken after death. The diagnosis can also be made from saliva, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid samples, but this is not as sensitive or reliable as brain samples.[61] Cerebral inclusion bodies called Negri bodies are 100% diagnostic for rabies infection but are found in only about 80% of cases.[32] If possible, the animal from which the bite was received should also be examined for rabies.[65]

Some light microscopy techniques may also be used to diagnose rabies at a tenth of the cost of traditional fluorescence microscopy techniques, allowing identification of the disease in less-developed countries.[66] A test for rabies, known as LN34, is easier to run on a dead animal's brain and might help determine who does and does not need post-exposure prevention.[67] The test was developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2018.[67]

The differential diagnosis in a case of suspected human rabies may initially include any cause of encephalitis, in particular infection with viruses such as herpesviruses, enteroviruses, and arboviruses such as West Nile virus. The most important viruses to rule out are herpes simplex virus type one, varicella zoster virus, and (less commonly) enteroviruses, including coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, polioviruses, and human enteroviruses 68 to 71.[68]

New causes of viral encephalitis are also possible, as was evidenced by the 1999 outbreak in Malaysia of 300 cases of encephalitis with a mortality rate of 40% caused by Nipah virus, a newly recognized paramyxovirus.[69] Likewise, well-known viruses may be introduced into new locales, as is illustrated by the outbreak of encephalitis due to West Nile virus in the eastern United States.[70]

Prevention

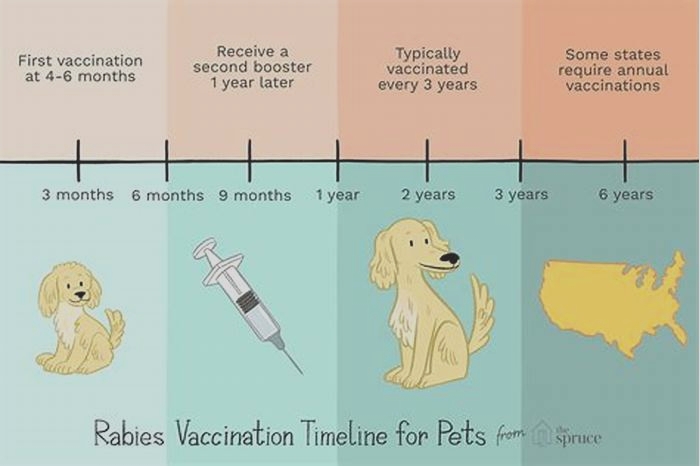

Almost all human exposure to rabies was fatal until a vaccine was developed in 1885 by Louis Pasteur and mile Roux. Their original vaccine was harvested from infected rabbits, from which the virus in the nerve tissue was weakened by allowing it to dry for five to ten days.[71] Similar nerve tissue-derived vaccines are still used in some countries, as they are much cheaper than modern cell culture vaccines.[72]

The human diploid cell rabies vaccine was started in 1967. Less expensive purified chicken embryo cell vaccine and purified vero cell rabies vaccine are now available.[65] A recombinant vaccine called V-RG has been used in Belgium, France, Germany, and the United States to prevent outbreaks of rabies in undomesticated animals.[73] Immunization before exposure has been used in both human and nonhuman populations, where, as in many jurisdictions, domesticated animals are required to be vaccinated.[74]

The Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services Communicable Disease Surveillance 2007 Annual Report states the following can help reduce the risk of contracting rabies:[75]

- Vaccinating dogs, cats, and ferrets against rabies

- Keeping pets under supervision

- Not handling wild animals or strays

- Contacting an animal control officer upon observing a wild animal or a stray, especially if the animal is acting strangely

- If bitten by an animal, washing the wound with soap and water for 10 to 15 minutes and contacting a healthcare provider to determine if post-exposure prophylaxis is required

28 September is World Rabies Day, which promotes the information, prevention, and elimination of the disease.[76]

In Asia and in parts of the Americas and Africa, dogs remain the principal host. Mandatory vaccination of animals is less effective in rural areas. Especially in developing countries, pets may not be privately kept and their destruction may be unacceptable. Oral vaccines can be safely distributed in baits, a practice that has successfully reduced rabies in rural areas of Canada, France, and the United States. In Montreal, Quebec, Canada, baits are successfully used on raccoons in the Mount-Royal Park area. Vaccination campaigns may be expensive, but cost-benefit analysis suggests baits may be a cost-effective method of control.[77] In Ontario, a dramatic drop in rabies was recorded when an aerial bait-vaccination campaign was launched.[78]

The number of recorded human deaths from rabies in the United States has dropped from 100 or more annually in the early 20th century to one or two per year due to widespread vaccination of domestic dogs and cats and the development of human vaccines and immunoglobulin treatments. Most deaths now result from bat bites, which may go unnoticed by the victim and hence untreated.[79]

Treatment

After exposure

Treatment after exposure can prevent the disease if given within 10 days. The rabies vaccine is 100% effective if given before symptoms of rabies appear.[32][34][80] Every year, more than 15million people get vaccinated after potential exposure. While this works well, the cost is significant.[81] In the US it is recommended people receive one dose of human rabies immunoglobulin (HRIG) and four doses of rabies vaccine over a 14-day period.[82] HRIG is expensive and makes up most of the cost of post-exposure treatment, ranging as high as several thousand dollars.[83] In the UK, one dose of HRIG costs the National Health Service 1,000,[84] although this is not flagged as a "high-cost medication".[85] A full course of vaccine costs 120180.[86] As much as possible of HRIG should be injected around the bites, with the remainder being given by deep intramuscular injection at a site distant from the vaccination site.[34]

People who have previously been vaccinated against rabies do not need to receive the immunoglobulinonly the postexposure vaccinations on days 0 and 3.[87] The side effects of modern cell-based vaccines are similar to the side effects of flu shots. The old nerve-tissue-based vaccination required multiple injections into the abdomen with a large needle but is inexpensive.[88] It is being phased out and replaced by affordable World Health Organization intradermal-vaccination regimens.[65] In children less than a year old, the lateral thigh is recommended.[89]

Thoroughly washing the wound as soon as possible with soap and water for approximately five minutes is effective in reducing the number of viral particles.[90] Povidone-iodine or alcohol is then recommended to reduce the virus further.[91]

Awakening to find a bat in the room, or finding a bat in the room of a previously unattended child or mentally disabled or intoxicated person, is an indication for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). The recommendation for the precautionary use of PEP in bat encounters where no contact is recognized has been questioned in the medical literature, based on a costbenefit analysis.[92] However, a 2002 study has supported the protocol of precautionary administration of PEP where a child or mentally compromised individual has been alone with a bat, especially in sleep areas, where a bite or exposure may occur with the victim being unaware.[93]

After onset

Once rabies develops, death almost certainly follows. Palliative care in a hospital setting is recommended with administration of large doses of pain medication, and sedatives in preference to physical restraint. Ice fragments can be given by mouth for thirst, but there is no good evidence intravenous hydration is of benefit.[94]

A treatment known as the Milwaukee protocol, which involves putting a person into a chemically induced coma and using antiviral medications, has been proposed.[95] It initially came into use in 2003, following Jeanna Giese, a teenage girl from Wisconsin, becoming the first person known to have survived rabies without preventive treatments before symptom onset.[96][97] The protocol has been tried multiple times since, but has been assessed as an ineffective treatment, and concerns raised about the costs and ethics of its use.[95][98]

Prognosis

Vaccination after exposure, PEP, is highly successful in preventing rabies.[80] In unvaccinated humans, rabies is almost certainly fatal after neurological symptoms have developed.[99]

Epidemiology

In 2010, an estimated 26,000 people died from rabies, down from 54,000 in 1990.[100] The majority of the deaths occurred in Asia and Africa.[99] As of 2015[update], India (approximately 20,847), followed by China (approximately 6,000) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (5,600), had the most cases.[101] A 2015 collaboration between the World Health Organization, World Organization of Animal Health (OIE), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation (FAO), and Global Alliance for Rabies Control has a goal of eliminating deaths from rabies by 2030.[102]

India

India has the highest rate of human rabies in the world, primarily because of stray dogs,[103] whose number has greatly increased since a 2001 law forbade the killing of dogs.[104] Effective control and treatment of rabies in India is hindered by a form of mass hysteria known as puppy pregnancy syndrome (PPS). Dog bite victims with PPS, male as well as female, become convinced that puppies are growing inside them, and often seek help from faith healers rather than medical services.[105] An estimated 20,000 people die every year from rabies in India, more than a third of the global total.[104]

Australia

Australia has an official rabies-free status,[106] although Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), discovered in 1996, is a rabies-causing virus related to the rabies virus prevalent in Australian native bat populations.

United States

Canine-specific rabies has been eradicated in the United States, but rabies is common among wild animals, and an average of 100 dogs become infected from other wildlife each year.[107][108]

Due to high public awareness of the virus, efforts at vaccination of domestic animals and curtailment of feral populations, and availability of postexposure prophylaxis, incidence of rabies in humans is very rare in the United States. From 1960 to 2018, a total of 125 human rabies cases were reported in the United States; 36 (28%) were attributed to dog bites during international travel.[109] Among the 89 infections acquired in the United States, 62 (70%) were attributed to bats.[109] The most recent rabies death in the United States was in November 2021, where a Texas child was bitten by a bat in late August 2021 but his parents failed to get him treatment. He died less than three months later.[110]

Europe

Either no or very few cases of rabies are reported each year in Europe; cases are contracted both during travel and in Europe.[111]

In Switzerland the disease was virtually eliminated after scientists placed chicken heads laced with live attenuated vaccine in the Swiss Alps.[78] Foxes, proven to be the main source of rabies in the country, ate the chicken heads and became immunized.[78][112]

Italy, after being declared rabies-free from 1997 to 2008, has witnessed a reemergence of the disease in wild animals in the Triveneto regions (Trentino-Alto Adige/Sdtirol, Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia), due to the spreading of an epidemic in the Balkans that also affected Austria. An extensive wild animal vaccination campaign eliminated the virus from Italy again, and it regained the rabies-free country status in 2013, the last reported case of rabies being reported in a red fox in early 2011.[113][114]

The United Kingdom has been free of rabies since the early 20th century except for a rabies-like virus (EBLV-2) in a few Daubenton's bats. There has been one fatal case of EBLV-2 transmission to a human.[115] There have been four deaths from rabies, transmitted abroad by dog bites, since 2000. The last infection in the UK occurred in 1922, and the last death from indigenous rabies was in 1902.[116][117]

Sweden and mainland Norway have been free of rabies since 1886.[118] Bat rabies antibodies (but not the virus) have been found in bats.[119] On Svalbard, animals can cross the arctic ice from Greenland or Russia.

Mexico

Mexico was certified by the World Health Organization as being free of dog-transmitted rabies in 2019 because no case of dog-human transmission had been recorded in two years.[120]

Asian Countries

Despite rabies being preventable and the many successes of the years from countries such as North America, South Korea and Western Europe, Rabies remains an endemic in many Southeast Asian countries including Cambodia, Bangladesh, Bhutan, North Korea, India, Indonesian, Myanmar Nepal, Shi Lanka, and Thailand[121]. Half the global rabies deaths occur in southeast Asia- approx. 26,000 per year.[122]

South Asia's Struggle to combat rabiesMuch of what prevents Asia from implementing the same measure as other countries is cost[123] . Known knowledge suggests treating wild canines is the primary source of resolving rabies, however it cost 10x more than treating individuals as they come with bites. Rabies research and treatment in general is so expensive that India and other surrounding countries are simply unable to apply many preventative measures due to financial restrictions.[124]

Thailand

In 2013 human rabies was nearly eradicated in the state of Thailand due to new measures put into place requiring the vaccination of all domestic dogs as well as programs seeking to vaccinate wild dogs and large animals. (Suwanpakdee. 2021)[125], however due to neighboring countries- Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar- and their inability to financially combat rabies, infected animals continue to pass the boarder and infect the Thai people leading to ~100 cases a year[126]. These areas around the boarder are called Rabies Red areas and its where Thailand continuously struggles with eradication and will do so until something is done in the surrounding countries (Suwanpakdee, S.2021).[127]

Thailand has the resources and medicine necessary to tackle rabies such as implementing regulations that require all children to receive a rabies vaccination before attending schools and having clinics available for those bit or scratched by a possible rabid animal. However, it is up to the individual to take themselves to the clinic, and 10 people per year die due to their own refusal.[128]

Cambodia

Cambodia has about 800 cases of human rabies per year making Cambodia one of the top countries in human rabies incidences.[129] Much of this falls on their lack of animal care, Cambodia has hundreds of thousands of animals infected with rabies, another global high, yet little surveillance of said animals and few laws requiring pets and other household animals to be vaccinated. (Baron N., Chevalier V.,Sowath L. et al(2022). What's striking about this is Cambodias national net worth, they are considered a wealthy nation with the funds capable of combating rabies and vaccinating all consenting citizens. In recent years Cambodia has improved significantly in their human rabies medical practices, with clinics all over the countries being made with treatments and vaccination on hand as well as rabies related education in school classes.[130] However, they are still lacking in terms of animal surveillance and treatment which leads to bleeding into surrounding countries.[131]

History

Rabies has been known since around 2000 BC.[132] The first written record of rabies is in the Mesopotamian Codex of Eshnunna (c.1930 BC), which dictates that the owner of a dog showing symptoms of rabies should take preventive measures against bites. If another person were bitten by a rabid dog and later died, the owner was heavily fined.[133]

In Ancient Greece, rabies was supposed to be caused by Lyssa, the spirit of mad rage.[134]

Ineffective folk remedies abounded in the medical literature of the ancient world. The physician Scribonius Largus prescribed a poultice of cloth and hyena skin; Antaeus recommended a preparation made from the skull of a hanged man.[135]

Rabies appears to have originated in the Old World, the first epizootic in the New World occurring in Boston in 1768.[136]

Rabies was considered a scourge for its prevalence in the 19th century. In France and Belgium, where Saint Hubert was venerated, the "St Hubert's Key" was heated and applied to cauterize the wound. By an application of magical thinking, dogs were branded with the key in hopes of protecting them from rabies.

It was not uncommon for a person bitten by a dog merely suspected of being rabid to commit suicide or to be killed by others.[21]

In ancient times the attachment of the tongue (the lingual frenulum, a mucous membrane) was cut and removed, as this was where rabies was thought to originate. This practice ceased with the discovery of the actual cause of rabies.[36] Louis Pasteur's 1885 nerve tissue vaccine was successful, and was progressively improved to reduce often severe side-effects.[22]

In modern times, the fear of rabies has not diminished, and the disease and its symptoms, particularly agitation, have served as an inspiration for several works of zombie or similarly themed fiction, often portraying rabies as having mutated into a stronger virus which fills humans with murderous rage or incurable illness, bringing about a devastating, widespread pandemic.[137]

Semi-Recent Unique Cases in Human Rabies

Human to Human transmission via cornea transplant

In 1978 a patient was admitted to the ER with rapid sensory and movement loss, loss of eyesight, muscle spasms, cardiac arrest, and lung failure and soon thereafter died. He was later misdiagnosed with Guillain-Barre syndrome and was cleared for a corneal transplant that was given to a woman who soon died of the same symptoms. Both bodies were then tested for multiple different diseases before being diagnosed with rabies. This is extremely rare due to the typical transplant precautionary measure and is currently known to be the only human to human case of rabies in the United States. [139]

Recent fatal cases in US

An 84-year-old man, residing in Minnesota passed in 2023 due to rabies from a bat kept by both him and his wife, as a precautionary measure he immediately took the bat in for testing and was promptly treated for rabies however despite this timely treatment, he passed from the virus. This is through to be an extremely rare case in American medicine as human rabies has been eradicated for many years in the US, however it is thought that the treatment this man received wasn't through enough for doctors to treat him properly, without a blood sample they were unaware of how prevalent it was in his blood stream and gave him an insufficient amount of medication needed to halt the progression of the disease. [140]

25-year case in the Southwestern state of India, Goa.

a 48-year-old male in southwest India was diagnosed with rabies near 25 years after contracting the virus, the incubation period for rabies was thought to be three months tops, however his lasted near 20 years before his death. histology and immunocytochemical demonstration of rabies viral antigen led to a diagnosis which was conducted following a suit for alleged medical negligence to the forensic department. The case manifested initially with hydrophobia and aggressive behavior, although was able drink a small amount of water throughout the day during lull periods in symptom manifestation. [141]

Other animals

Rabies is infectious to mammals; three stages of central nervous system infection are recognized. The clinical course is often shorter in animals than in humans, but result in similar symptoms and almost always death. The first stage is a one- to three-day period characterized by behavioral changes and is known as the prodromal stage. The second is the excitative stage, which lasts three to four days. This stage is often known as "furious rabies" for the tendency of the affected animal to be hyper-reactive to external stimuli and bite or attack anything near. In some cases, animals skip the excitative stage and develop paralysis, as in the third phase; the paralytic phase. This stage develops due to damage to motor neurons. Incoordination is seen, owing to rear limb paralysis, and drooling and difficulty swallowing is caused by paralysis of facial and throat muscles. Death is usually caused by respiratory arrest.[142]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Rabies Fact Sheet N99". World Health Organization. July 2013. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "Rabies - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ "Rabies". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "Rabies, Australian bat lyssavirus and other lyssaviruses". The Department of Health. December 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Rabies diagnosis and treatment=27 June 2023". Mayo clinic.

- ^ a b "Rabies". CDC. 29 July 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Rabies, Symptoms, Causes, Treatment". Medical News Today. 15 November 2017.

- ^ "Rabies, Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ "Animal bites and rabies". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 27 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d Cotran RS, Kumar V, Fausto N (2005). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (7thed.). Elsevier/Saunders. p.1375. ISBN978-0-7216-0187-8.

- ^ a b c Tintinalli JE (2010). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). McGraw-Hill. pp.Chapter 152. ISBN978-0-07-148480-0.

- ^ Wunner WH (2010). Rabies: Scientific Basis of the Disease and Its Management. Academic Press. p.556. ISBN978-0-08-055009-1.

- ^ Manoj S, Mukherjee A, Johri S, Kumar KV (2016). "Recovery from rabies, a universally fatal disease". Military Medical Research. 3 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/s40779-016-0089-y. PMC4947331. PMID27429788.

- ^ Weyer J, Msimang-Dermaux V, Paweska JT, Blumberg LH, Le Roux K, Govender P, etal. (9 June 2016). "A case of human survival of rabies, South Africa". Southern African Journal of Infectious Diseases. 31 (2): 6668. doi:10.1080/23120053.2016.1128151. hdl:2263/59121. ISSN2312-0053.

- ^ Gilbert AT, Petersen BW, Recuenco S, Niezgoda M, Gmez J, Laguna-Torres VA, Rupprecht C (August 2012). "Evidence of rabies virus exposure among humans in the Peruvian Amazon". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 87 (2): 206215. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0689. PMC3414554. PMID22855749.

- ^ "Rabies: The Facts" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: second report (PDF) (2ed.). Geneva: WHO. 2013. p.3. ISBN978-92-4-120982-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Rabies-Free Countries and Political Units". CDC. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Simpson DP (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5ed.). London: Cassell. p.883. ISBN978-0-304-52257-6.

- ^ a b Rotivel Y (1995). Rupprecht CE, Smith JS, Fekadu M, Childs JE (eds.). "Introduction: The ascension of wildlife rabies: a cause for public health concern or intervention?". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1 (4): 10714. doi:10.3201/eid0104.950401. PMC2626887. PMID8903179. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Giesen A, Gniel D, Malerczyk C (March 2015). "30 Years of rabies vaccination with Rabipur: a summary of clinical data and global experience". Expert Review of Vaccines (Review). 14 (3): 35167. doi:10.1586/14760584.2015.1011134. PMID25683583.

- ^ Rupprecht CE, Willoughby R, Slate D (December 2006). "Current and future trends in the prevention, treatment and control of rabies". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 4 (6): 102138. doi:10.1586/14787210.4.6.1021. PMID17181418. S2CID36979186.

- ^ Cliff AD, Haggett P, Smallman-Raynor M (2004). World atlas of epidemic diseases. London: Arnold. p.51. ISBN978-0-340-76171-7.

- ^ "Rabies". AnimalsWeCare.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014.

- ^ "How does rabies cause aggression?". medicalnewstoday.com. Medical News Today. 14 October 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Wilson PJ, Rohde RE, Oertli EH, Willoughby Jr RE (2019). Rabies: Clinical Considerations and Exposure Evaluations (1sted.). Elsevier. p.28. ISBN978-0-323-63979-8. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "How Do You Know if an Animal Has Rabies? | CDC Rabies and Kids". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "Rabies (for Parents)". KidsHealth.org. Nemours KidsHealth. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "Symptoms of rabies". NHS.uk. 12 June 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ van Thiel PP, de Bie RM, Eftimov F, Tepaske R, Zaaijer HL, van Doornum GJ, etal. (July 2009). "Fatal human rabies due to Duvenhage virus from a bat in Kenya: failure of treatment with coma-induction, ketamine, and antiviral drugs". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 3 (7): e428. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000428. PMC2710506. PMID19636367.

- ^ a b c Drew WL (2004). "Chapter 41: Rabies". In Ryan KJ, Ray CG (eds.). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4thed.). McGraw Hill. pp.597600. ISBN978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ^ Finke S, Conzelmann KK (August 2005). "Replication strategies of rabies virus". Virus Research. 111 (2): 12031. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2005.04.004. PMID15885837.

- ^ a b c d e "Rabies Post-Exposure Prophylaxis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 23 December 2009. Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ Gluska S, Zahavi EE, Chein M, Gradus T, Bauer A, Finke S, Perlson E (August 2014). "Rabies Virus Hijacks and accelerates the p75NTR retrograde axonal transport machinery". PLOS Pathogens. 10 (8): e1004348. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004348. PMC4148448. PMID25165859.

- ^ a b Baer G (1991). The Natural History of Rabies. CRC Press. ISBN978-0-8493-6760-1. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Shannon LM, Poulton JL, Emmons RW, Woodie JD, Fowler ME (April 1988). "Serological survey for rabies antibodies in raptors from California". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 24 (2): 2647. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-24.2.264. PMID3286906.

- ^ Gough PM, Jorgenson RD (July 1976). "Rabies antibodies in sera of wild birds". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 12 (3): 3925. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-12.3.392. PMID16498885.

- ^ Jorgenson RD, Gough PM, Graham DL (July 1976). "Experimental rabies in a great horned owl". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 12 (3): 4447. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-12.3.444. PMID16498892. S2CID11374356.

- ^ Wong D. "Rabies". Wong's Virology. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ^ Campbell JB, Charlton K (1988). Developments in Veterinary Virology: Rabies. Springer. p.48. ISBN978-0-89838-390-4.

- ^ "Rabies". World Health Organization. 21 April 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Pawan JL (1959). "The transmission of paralytic rabies in Trinidad by the vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus murinus) Wagner". Caribbean Medical Journal. 21: 11036. PMID13858519.

- ^ Pawan JL (1959). "Rabies in the vampire bat of Trinidad, with special reference to the clinical course and the latency of infection". Caribbean Medical Journal. 21: 13756. PMID14431118.

- ^ Taylor PJ (December 1993). "A systematic and population genetic approach to the rabies problem in the yellow mongoose (Cynictis penicillata)". The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 60 (4): 37987. PMID7777324.

- ^ "Rabies. Other Wild Animals: Terrestrial carnivores: raccoons, skunks and foxes". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC). Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ Anderson J, Frey R (2006). "Rabies". In Fundukian LJ (ed.). Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine (3rded.).

- ^ McRuer DL, Jones KD (May 2009). "Behavioral and nutritional aspects of the Virginian opossum (Didelphis virginiana)". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 12 (2): 21736, viii. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2009.01.007. PMID19341950.

- ^ Gaughan JB, Hogan LA, Wallage A (2015). Abstract: Thermoregulation in marsupials and monotremes, chapter of Marsupials and monotremes: nature's enigmatic mammals. Nova Science Publishers, Incorporated. ISBN978-1-63483-487-2. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ The Merck Manual (11thed.). 1983. p.183.

- ^ The Merck manual of Medical Information (Second Homeed.). 2003. p.484.

- ^ Turton J (2000). "Rabies: a killer disease". National Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 23 September 2006.

- ^ Jackson AC, Wunner WH (2002). Rabies. Academic Press. p.290. ISBN978-0-12-379077-4. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014.

- ^ Lynn DJ, Newton HB, Rae-Grant AD (2012). The 5-Minute Neurology Consult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp.414. ISBN978-1-4511-0012-9.

- ^ Davis LE, King MK, Schultz JL (15 June 2005). Fundamentals of neurologic disease. Demos Medical Publishing. p.73. ISBN978-1-888799-84-2. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014.

- ^ "Rabies FAQs: Exposure, prevention and treatment". RabiesAlliance.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016.

- ^ Srinivasan A, Burton EC, Kuehnert MJ, Rupprecht C, Sutker WL, Ksiazek TG, etal. (March 2005). "Transmission of rabies virus from an organ donor to four transplant recipients". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 110311. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043018. PMID15784663.

- ^ "Human Rabies Prevention --- United States, 2008 Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 23 May 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Kahn CM, Line S, eds. (2010). The Merck Veterinary Manual (10thed.). Kendallville, Indiana: Courier Kendallville, Inc. p.1193. ISBN978-0-911910-93-3.

- ^ Dean DJ, Abelseth MK (1973). "Ch. 6: The fluorescent antibody test". In Kaplan MM, Koprowski H (eds.). Laboratory techniques in rabies. Monograph series. Vol.23 (3rded.). World Health Organization. p.73. ISBN978-92-4-140023-7.

- ^ a b Fooks AR, Johnson N, Freuling CM, Wakeley PR, Banyard AC, McElhinney LM, etal. (September 2009). "Emerging technologies for the detection of rabies virus: challenges and hopes in the 21st century". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 3 (9): e530. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000530. PMC2745658. PMID19787037.

- ^ Tordo N, Bourhy H, Sacramento D (1994). "Ch. 10: PCR technology for lyssavirus diagnosis". In Clewley JP (ed.). The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for Human Viral Diagnosis. CRC Press. pp.125145. ISBN978-0-8493-4833-4.

- ^ David D, Yakobson B, Rotenberg D, Dveres N, Davidson I, Stram Y (June 2002). "Rabies virus detection by RT-PCR in decomposed naturally infected brains". Veterinary Microbiology. 87 (2): 1118. doi:10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00041-x. PMID12034539.

- ^ Biswal M, Ratho R, Mishra B (September 2007). "Usefulness of reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for detection of rabies RNA in archival samples". Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 60 (5): 2989. doi:10.7883/yoken.JJID.2007.298. PMID17881871.

- ^ a b c Ly S, Buchy P, Heng NY, Ong S, Chhor N, Bourhy H, Vong S (September 2009). Carabin H (ed.). "Rabies situation in Cambodia". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 3 (9): e511. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000511. PMC2731168. PMID19907631. e511.

- ^ Drr S, Nassengar S, Mindekem R, Diguimbye C, Niezgoda M, Kuzmin I, etal. (March 2008). Cleaveland S (ed.). "Rabies diagnosis for developing countries". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (3): e206. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000206. PMC2268742. PMID18365035. e206.

- ^ a b "New Rapid Rabies Test Could Revolutionize Testing and Treatment | CDC Online Newsroom | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Rabies: Differential Diagnoses & Workup". eMedicine Infectious Diseases. 3 October 2008. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ Taylor DH, Straw BE, Zimmerman JL, D'Allaire S (2006). Diseases of swine. Oxford: Blackwell. pp.4635. ISBN978-0-8138-1703-3. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ Minagar A, Alexander JS (2005). Inflammatory Disorders Of The Nervous System: Pathogenesis, Immunology, and Clinical Management. Humana Press. ISBN978-1-58829-424-1.

- ^ Geison GL (April 1978). "Pasteur's work on rabies: reexamining the ethical issues". The Hastings Center Report. 8 (2): 2633. doi:10.2307/3560403. JSTOR3560403. PMID348641.

- ^ Srivastava AK, Sardana V, Prasad K, Behari M (March 2004). "Diagnostic dilemma in flaccid paralysis following anti-rabies vaccine". Neurology India. 52 (1): 1323. PMID15069272. Archived from the original on 2 August 2009.

- ^ Reece JF, Chawla SK (September 2006). "Control of rabies in Jaipur, India, by the sterilisation and vaccination of neighbourhood dogs". The Veterinary Record. 159 (12): 37983. doi:10.1136/vr.159.12.379. PMID16980523. S2CID5959305.

- ^ "Compendium of Animal Rabies Prevention and Control" (PDF). National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians. 31 December 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ 2007 Annual Report (PDF) (Report). Bureau of Communicable Disease Control and Prevention. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ "World Rabies Day". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 31 December 2011.

- ^ Meltzer MI (OctoberDecember 1996). "Assessing the costs and benefits of an oral vaccine for raccoon rabies: a possible model". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2 (4): 3439. doi:10.3201/eid0204.960411. PMC2639934. PMID8969251.

- ^ a b c Grambo RL (1995). The World of the Fox. Vancouver: Greystone Books. pp.945. ISBN978-0-87156-377-4.

- ^ "Rabies in the U.S." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 April 2011. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ a b Lite J (8 October 2008). "Medical Mystery: Only One Person Has Survived Rabies without VaccineBut How?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 5 November 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ "Human rabies: better coordination and emerging technology to improve access to vaccines". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Use of a Reduced (4-Dose) Vaccine Schedule for Postexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent Human Rabie" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Cost of Rabies Prevention". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 June 2019. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016.

- ^ "BNF via NICE is only available in the UK". The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. UK.

- ^ "Rabies immunoglobulin". Milton Keynes Formulary Formulary.

- ^ "Rabies - Vaccination". National Health Services (NHS). UK. 23 October 2017.

- ^ Park K (2013). Park's Textbook of Prentive and Social Medicine (22nded.). Banarsidas Bhanot, Jabalpur. p.254. ISBN978-93-82219-02-6.

- ^ Hicks DJ, Fooks AR, Johnson N (September 2012). "Developments in rabies vaccines". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 169 (3): 199204. doi:10.1093/clinids/13.4.644. PMC3444995. PMID22861358.

- ^ "Rabies". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Rabies & Australian bat lyssavirus information sheet". Health.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ National Center for Disease Control (2014). "National Guidelines on Rabies Prophylaxis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ De Serres G, Skowronski DM, Mimault P, Ouakki M, Maranda-Aubut R, Duval B (June 2009). "Bats in the bedroom, bats in the belfry: reanalysis of the rationale for rabies postexposure prophylaxis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (11): 14931499. doi:10.1086/598998. PMID19400689.

- ^ Despond O, Tucci M, Decaluwe H, Grgoire MC, S Teitelbaum J, Turgeon N (March 2002). "Rabies in a nine-year-old child: The myth of the bite". The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 13 (2): 121125. doi:10.1155/2002/475909. PMC2094861. PMID18159381.

- ^ Jackson AC (2020). "Chapter 17: Therapy of human rabies". In Jackson AC, Fooks AR (eds.). Rabies Scientific Basis of the Disease and Its Management (4thed.). Elsevier Science. p.561. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818705-0.00017-0. ISBN978-0-12-818705-0. S2CID240895449.

- ^ a b Jackson AC (2016). "Human Rabies: a 2016 Update". Curr Infect Dis Rep (Review). 18 (11): 38. doi:10.1007/s11908-016-0540-y. PMID27730539. S2CID25702043.

- ^ Jordan Lite (8 October 2008). "Medical Mystery: Only One Person Has Survived Rabies without Vaccine--But How?". Scientific American. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ Rodney E. Willoughby Jr., online "A Cure for Rabies?" Scientific American, V. 256, No. 4, April 2007, p. 95.

- ^ Zeiler FA, Jackson AC (2016). "Critical Appraisal of the Milwaukee Protocol for Rabies: This Failed Approach Should Be Abandoned". Can J Neurol Sci (Review). 43 (1): 4451. doi:10.1017/cjn.2015.331. PMID26639059.

- ^ a b "Rabies". World Health Organization (WHO). September 2011. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, etal. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMC10790329. PMID23245604. S2CID1541253.

- ^ Hampson K, Coudeville L, Lembo T, Sambo M, Kieffer A, Attlan M, etal. (April 2015). "Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (4): e0003709. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003709. PMC4400070. PMID25881058.

- ^ "Rabies". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Dugan E (30 April 2008). "Dead as a dodo? Why scientists fear for the future of the Asian vulture". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

India now has the highest rate of human rabies in the world.

- ^ a b Harris G (6 August 2012). "Where Streets Are Thronged With Strays Baring Fangs". New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "Medicine challenges Indian superstition". DW.DE. 31 December 2012. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013.

- ^ "Essential rabies maps". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 17 February 2010.

- ^ "CDC Rabies Surveillance in the U.S.: Human Rabies Rabies". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ Fox M (7 September 2007). "U.S. free of canine rabies virus". Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

"We don't want to misconstrue that rabies has been eliminated dog rabies virus has been," CDC rabies expert Dr. Charles Rupprecht told Reuters in a telephone interview.

- ^ a b Pieracci EG, Pearson CM, Wallace RM, Blanton JD, Whitehouse ER, Ma X, etal. (June 2019). "Vital Signs: Trends in Human Rabies Deaths and Exposures - United States, 1938-2018". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (23): 524528. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6823e1. PMC6613553. PMID31194721.

- ^ Blackburn D (2022). "Human Rabies Texas, 2021". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 71 (49): 15471549. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7149a2. ISSN0149-2195. PMC9762899. PMID36480462.

- ^ "Surveillance Report - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2015 - Rabies" (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Switzerland ended rabies epidemic by air dropping vaccinated chicken heads from helicopters". thefactsource.com. 20 November 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Rabies in Africa: The RESOLAB network". 29 June 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ "Ministero della Salute: "Italia indenne dalla rabbia". l'Ultimo caso nel 2011 - Quotidiano Sanit". Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ "Man dies from rabies after bat bite". BBC News. 24 November 2002.

- ^ "Rabies". NHS. 23 February 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Q&A: Rabies". BBC News. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Mehnert E (1988). "Rabies och bekmpningstgrder i 1800-talets Sverige" [Rabies and remedies in 19th century Sweden]. Svensk veterinrtidning [Swedish veterinary magazine] (in Swedish). 1988/40. Sveriges veterinrfrbund: 27788.

- ^ "Fladdermusrabies" [Bat rabies]. Statens Veterinrmedicinska Anstalt [State Veterinary Medical Institution] (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ "Cmo Mxico se convirti en el primer pas del mundo libre de rabia transmitida por perros" [How Mexico became the first country in the world free of rabies transmitted by dogs]. BBC News (in Spanish). 12 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ World Heath Organization. Rabies in the South-East Asia Region. 2024.https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/rabies#:~:text=In%20the%20South%2DEast%20Asia%20Region%2C%20rabies%20is%20endemic%20in,Nepal%2C%20Sri%20Lanka%20and%20Thailand.

- ^ Hicks, R. (2021) Rabies is Spreading in South Asia Fueled by Inequality and Neglect. https://www.eco-business.com/news/rabies-is-spreading-in-southeast-asia-fuelled-by-inequality-and-neglect/#:~:text=Rabies%20is%20endemic%20in%20eight,control%20in%20the%20regional%20bloc.

- ^ Abbas, S. S., & Kakkar, M. (2014). Rabies control in India: a need to close the gap between research and policy. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 93, 131-132. https://www.scielosp.org/article/bwho/2015.v93n2/131-132/en/

- ^ Chowdhury, F. R., Basher, A., Amin, M. R., Hassan, N., & Patwary, M. I. (2015). Rabies in South Asia: fighting for elimination. Recent patents on anti-infective drug discovery, 10(1), 3034. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574891x10666150410130024

- ^ Suwanpakdee, S. (2021). Current characteristics of animal rabies cases in Thailand and relevant risk factors identified by a spatial modeling approach. Natural Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information. 15(12) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009980

- ^ CDC. (2024) Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers' health. Thailand https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/thailand#:~:text=Rabid%20dogs%20are%20commonly%20found,rabies%20treatment%20is%20often%20available.&text=Since%20children%20are%20more%20likely,for%20children%20traveling%20to%20Thailand.

- ^ Suwanpakdee, S. (2021). Current characteristics of animal rabies cases in Thailand and relevant risk factors identified by a spatial modeling approach. Natural Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information. 15(12) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009980

- ^ CDC. (2024) Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers' health. Thailand https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/thailand#:~:text=Rabid%20dogs%20are%20commonly%20found,rabies%20treatment%20is%20often%20available.&text=Since%20children%20are%20more%20likely,for%20children%20traveling%20to%20Thailand.

- ^ Baron N., Chevalier V.,Sowath L. ,Veasna D. ,Dussart P.,Fontenille D.,Peng Y.S.,Martnez-Lpez B. (2022).Accessibility to rabies centers and human rabies post-exposure prophylaxis rates in Cambodia: A Bayesian spatio-temporal analysis to identify optimal locations for future centers. PLOS.Neglected Tropical Diseases https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010494

- ^ Center for Disease Control.(2024)Travelers' Health. Cambodia.https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/cambodia#:~:text=Rabid%20dogs%20are%20commonly%20found,rabies%20treatment%20is%20often%20available.&text=Since%20children%20are%20more%20likely,for%20children%20traveling%20to%20Cambodia.

- ^ Hicks, R. (2021) Rabies is Spreading in South Asia Fueled by Inequality and Neglect. https://www.eco-business.com/news/rabies-is-spreading-in-southeast-asia-fuelled-by-inequality-and-neglect/#:~:text=Rabies%20is%20endemic%20in%20eight,control%20in%20the%20regional%20bloc.

- ^ Adamson PB (1977). "The spread of rabies into Europe and the probable origin of this disease in antiquity". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 109 (2): 1404. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00133829. JSTOR25210880. PMID11632333. S2CID27354751.

- ^ Dunlop RH, Williams DJ (1996). Veterinary Medicine: An Illustrated History. Mosby. ISBN978-0-8016-3209-9.

- ^ "Rabies: an ancient disease". Gobierno de Mxico.

- ^ Barrett AD, Stanberry LR (2009). Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Academic Press. p.612. ISBN978-0-08-091902-7. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Baer GM (1991). The Natural History of Rabies (2nded.). CRC Press. ISBN978-0-8493-6760-1.

The first major epizootic in North America was reported in 1768, continuing until 1771 when foxes and dogs carried the disease to swine and domestic animals. The malady was so unusual that it was reported as a new disease

- ^ Than K (27 October 2010). "'Zombie Virus' Possible via Rabies-Flu Hybrid?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ Santo Toms Prez M (2002). La asistencia a los enfermos en Castilla en la Baja Edad Media. Universidad de Valladolid. pp.172173. ISBN84-688-3906-X via Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

- ^ Anderson LJ, Williams LP Jr, Layde JB, Dixon FR, Winkler WG. 1984 Nosocomial rabies: investigation of contacts of human rabies cases associated with a corneal transplant. Am J Public Health. 74(4):370-2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.4.370

- ^ Sudhakar. S (2023). Rabies patient becomes first fatal case in US after post-exposure treatment, report says. University Nebraska Medical Center. Global Center for Health Security. https://www.unmc.edu/healthsecurity/transmission/2023/04/04/rabies-patient-becomes-first-fatal-case-in-us-after-post-exposure-treatment-report-says/

- ^ Shankar, S. K., Mahadevan, A., Sapico, S. D., Ghodkirekar, M. S., Pinto, R. G., & Madhusudana, S. N. (2012). Rabies viral encephalitis with probable 25 year incubation period!. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 15(3), 221223. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-2327.99728

- ^ Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4thed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN978-0-7216-6795-9.

Further reading

- Pankhurst, Richard. "The history and traditional treatment of rabies in Ethiopia." Medical History 14, no. 4 (1970): 378389.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to

Rabies.

Look up

rabiesin Wiktionary, the free dictionary.